The first consciously organized expression of the Slovenian character in art

Slovene impressionism revealed itself for the first time in 1900, with the exhibition in Ljubljana of the works of four artists – Rihard Jakopič, Matija Jama, Ivan Grohar and Matej Sternen. Their ideas about art had taken shape in the stimulating milieu of the highly regarded Munich art school run by an influential expatriate Slovene, the artist and teacher Anton Ažbe, and they themselves were eager to win international recognition for Slovene painting. National consciousness had grown strong, and not only political but also literary and artistic figures sought freedom and an individual identity for their small country, then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

Reactions to the ‘new’ art – its political/national importance

The work of this core group of four had considerable impact on the art of the southern Slavs, yet the road to recognition was not always smooth. Their first exhibition was a success, but the second, held in 1902, was memorable for the public’s indifference and disparagement. Ironically it was this exhibition that clearly defined the four as impressionists and set the boundaries of Slovenian art.

The ‘failure’ was due essentially to a divergence of opinion, political as well as artistic, as to what constitutes memorable art, and how it could serve political or nationalistic ends. Some authorities were critical of both the impressionist technique and choice of motifs, which they thought lacked dignity. What they looked for was a traditional style with grand allegorical themes that would express the country’s maturing aspirations. But Rihard Jakopič uncompromisingly condemned the established academic painting as being artistically out of fashion and unchallenging. In his view, allegorical works were used as political tools, as propaganda for a morally feeble (and alien) governing society. Unfortunately, while not all comments on the exhibits were unfavourable, the support of those who considered the impressionists’ work to be of international standard led to the artists being labelled as ‘foreigners’ on the domestic scene, imitative and ‘un-slovenian’.

Nature in Impressionist art

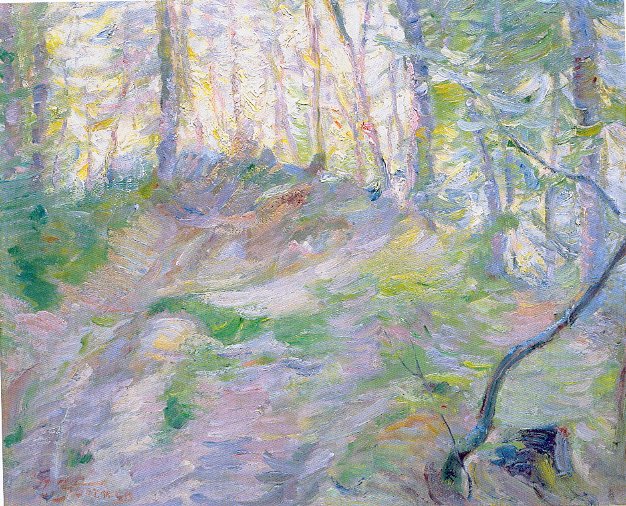

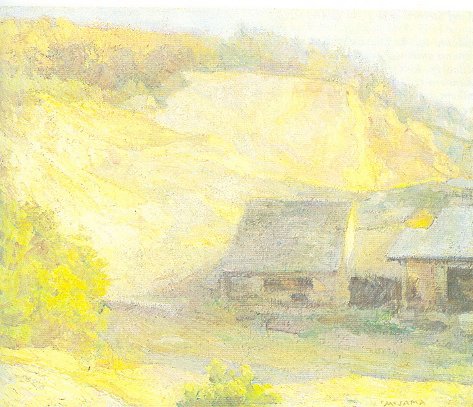

Although ‘Impressionism’ had developed from ‘plein-air’ naturalism in France it became the springboard for similar movements elsewhere in Europe. But nowhere had it succeeded in creating a school except at Škofja Loka, with Slovenes, who may have adopted the impressionist style of painting but did so two decades later, when Impressionism in France was already history, superseded by other ‘isms’. Moreover Slovenes struggled to master this technique independently of the French, and from a broader perspective, not seeing it as an end in itself but rather as a means to an end.

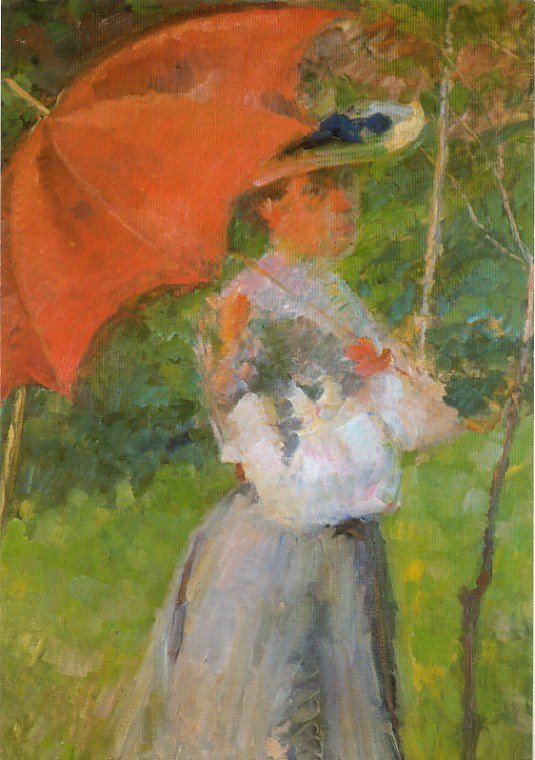

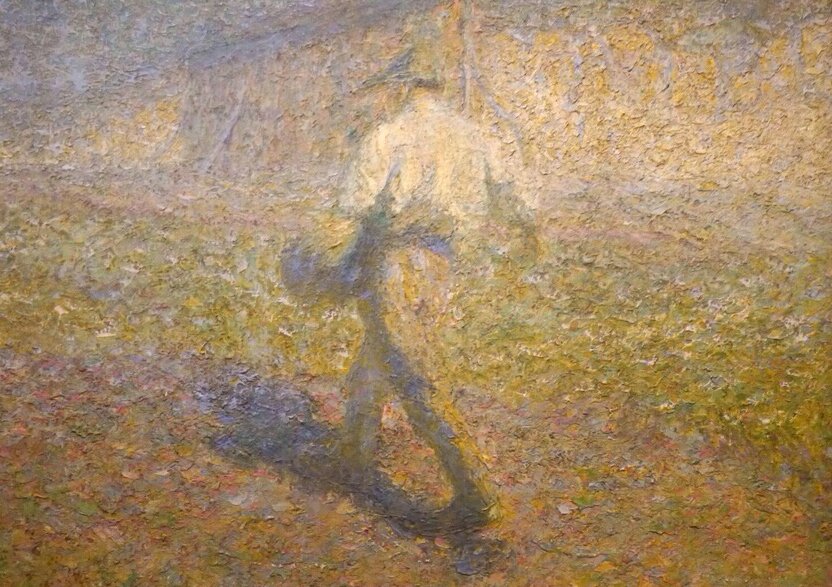

As Jakopič stated: ‘the repetition of nature does not satisfy me or my comrades. We have tried, in mastering this technique, to express the most profound revelations of the human soul.’ Their works indeed possess strong symbolic and expressionist qualities, while their style has been described as the first consciously organized expression of the Slovene character in art, its essential nature being lyrical, visionary and gently melancholy.

International exhibitions and success

The rejection of Slovenian impressionists by their own proved to be a blessing in disguise, as they were led to exhibit abroad, and to great effect. Their exhibition at Miethke’s gallery in Vienna in 1904 was a triumph, especially as Impressionism did not flourish well on Austrian soil: yet it was precisely within the Austrian political framework that the Slovenian group, under the name of the Sava Club, developed and experienced its first international success. Paradoxically, the critics there recognized what the Slovenian public had not: the originality of the works and their expression of the Slovenian mood, something also enthusiastically acknowledged by the Slovenian literary movement ‘Moderna’, with writers Ivan Cankar and Oton Župančič at its head. After the Vienna exhibition Jakopič was joined by his colleagues at Škofja Loka, which became the ‘Barbizon’ of Slovenian Impressionism. It was at this time that the group received the distinction of being considered a ‘school’.

They continued to exhibit, internationally as well as in the south Slav world, and were very well received – Belgrade in 1904, Sofia in 1906, 1907 Trieste, 1908 Zagreb, Warsaw and Cracow, 1911 Rome. The great exhibition of 1912 in Belgrade, just prior to the outbreak of war in the Balkans, was an important political manifestation of Jugoslav solidarity. The Slovenes again stood out, nevertheless, being visibly different from that of the others, indisputably the most compact artistic group there.

The first Slovenian Art Gallery and school

Much of the credit for this must go to Jakopič, who from the first had been accepted by all as the natural leader of the group, and had strong, well-defined ideas as to the role art and the artist played in society. He strove to establish their value in the life of a nation that had already experienced a political and literary awakening; realizing that to achieve the same for the visual arts, organizational and functional institutions were necessary, as well as a continuing contact with the public.

To this end Jakopič propagated the idea of a Slovenian Art Gallery, and in 1908 succeeded in building an exhibition pavilion after the plans of architect Max Fabiani. It was the first in Ljubljana and Slovenia. Every year the Gallery hosted an exhibition of Slovenian works, and occasionally also that of other nationals, Czech, Croatian and Serbian. An important event in the history was the 1910 exhibition, which for the first time attempted to depict the development of Slovene art in the 19th century. With this exhibition Impressionism took its place as a contributory force in the cultural development of the Slovene nation, and like literature, the visual arts were acknowledged to have been part of the historic process of the country’s national emancipation.

Jakopič’s policies also included the founding of an art school, which he organized together with colleague Matej Sternen. Although this partnership was short-lived, the school was successful in strengthening public interest in the visual arts as a viable cultural form.The First World War and end of the Sava Club

The members of the group had meanwhile gone their separate ways, developing their individual talents: and the Sava club, already affected by Grohar’s death in 1911 was weakened still further by the outbreak of the First World

War. During the peace negotiations in 1919 it took part in the Yugoslav Art Exhibition, launched an action for the foundation of an Academy of fine arts and tried to renew itself with younger members. Following an appearance in Zagreb in 1921, however, and another exhibition in Belgrade the year after, it finally ‘faded away’: with it (it seems) went the last echo of what we look on today as Slovene impressionism.

The artist’s perspective

The group disbanded, yet its work remained relevant. Jama saw Impressionism as a necessary stage in the development of art, although he realized it could not exist for its own sake. Nevertheless in the history of painting it had a special mission, and what it had discovered in the fields of light and colour would be the basis for future painting.