In the history of Slovenian people who occupy the land south of the Alps, and down as far as the port of Trieste and as far west as Venice, the 19th century represents a milestone in the development of their national consciousness. As a people Slovenes have striven for self-expression ever since the Protestant priest Primož Trubar translated the New Testament into Slovenian in the 16th century. This marked the beginning of the process at the end of which Slovenian emerged as a literary language. The work on the establishment of Slovenian language, grammar and dictionary continued during the following centuries, undertaken by a dedicated group of scholars.

Cultural advancements made during the early 19th century included the continuing envolvement of Slovenian national identity and Slovenian literary language through the efforts of men such as linguist Jernej Kopitar, literary critic Matija Čop, and poet France Prešeren. This period included; the first public address delivered in Slovenian, and the first public performance of Slovenian songs. Janez Bleiweis established a practical journal in 1843, Kmetijske in rokodelske novice (Farmer’s and Craftsmen’s News); influential in the Slovene national movement. It is through their efforts and considerable linguistic skills that they succeeded in raising Slovenian into a literary language comparable to the mainstream German, Italian, and French of Central Europe.

It was also in this period, and part of this movement, that great strides were made in the field of education. One of the most significant contributions to Slovenian education was made by Anton Martin Slomšek, a prominent Slovenian of the time. Born in 26 November 1800, the same year as France Prešeren, he was to be appointed to an exalted position as the Bishop of Lavant, but the work into which he put all his energy and undoubtedly great ability was Slovenian language education.

Anton Slomšek, later to become Anton Martin Slomšek, taking the name of his favorite Saint, was born and grew up on a prosperous farm in Styria. As the eldest son he was expected to take over the management of the farm and his father wanted to enroll him in the appropriate school for farmers’ sons. Anton’s frail and bookish mother had other ideas. She brought him up with love of books, Slovenian folklore and songs. She wanted her talented son to continue his education. In this she had the full support of his teachers and more importantly, the parish priest. Such promising boys were traditionally encouraged to undertake further education and received financial support by influential members of the community.

Anton was sent to complete his secondary schooling in the regional centre, Celje. He subsequently undertook tertiary studies in Ljubljana at The School of Theological and Philosophical Studies, where Slomšek and Prešeren were fellow students. Both chose Slovenian language as an elective subject. Later Prešeren went on to study law, and Slomšek, on his pathway to priesthood, enrolled in the Theological Studies. While each went their own way, Slomšek and Prešeren formed an enduring friendship based to a great extent on their common interest in and love of the Slovenian language and its standing in the Austrian Empire.

Following his ordination into priesthood in 1824 there were a number of appointments as chaplain and parish priest. Then, from 1829 to 1838 Slomšek was appointed Spiritual Director to the seminarians preparing for ordination in Klagenfurt, Carinthia. In this position his views on the crucial role of the parish priest matured and his stand on the use of Slovenian as the mother tongue of Slovenian people was reaffirmed and strengthened. He strongly believed that priests must preach and speak about matters of faith to people in their own native language rather than German. By speaking Slovenian matters of faith would be communicated and understood better. He also believed that education and literacy were essential. As such a great part of his work with the seminarians was not only to improve their own speaking and writing skills in Slovenian but also give them some training as teachers of Slovenian language.

Most importantly he advocated the establishment of Sunday schools, usually conducted by local priests, for country children to learn to read and write in Slovenian. This would be the only schooling available to them as they had to work during weekdays from a very early age, mostly by herding cattle and sheep. This initiative was invaluable in raising the literacy level among the general population.

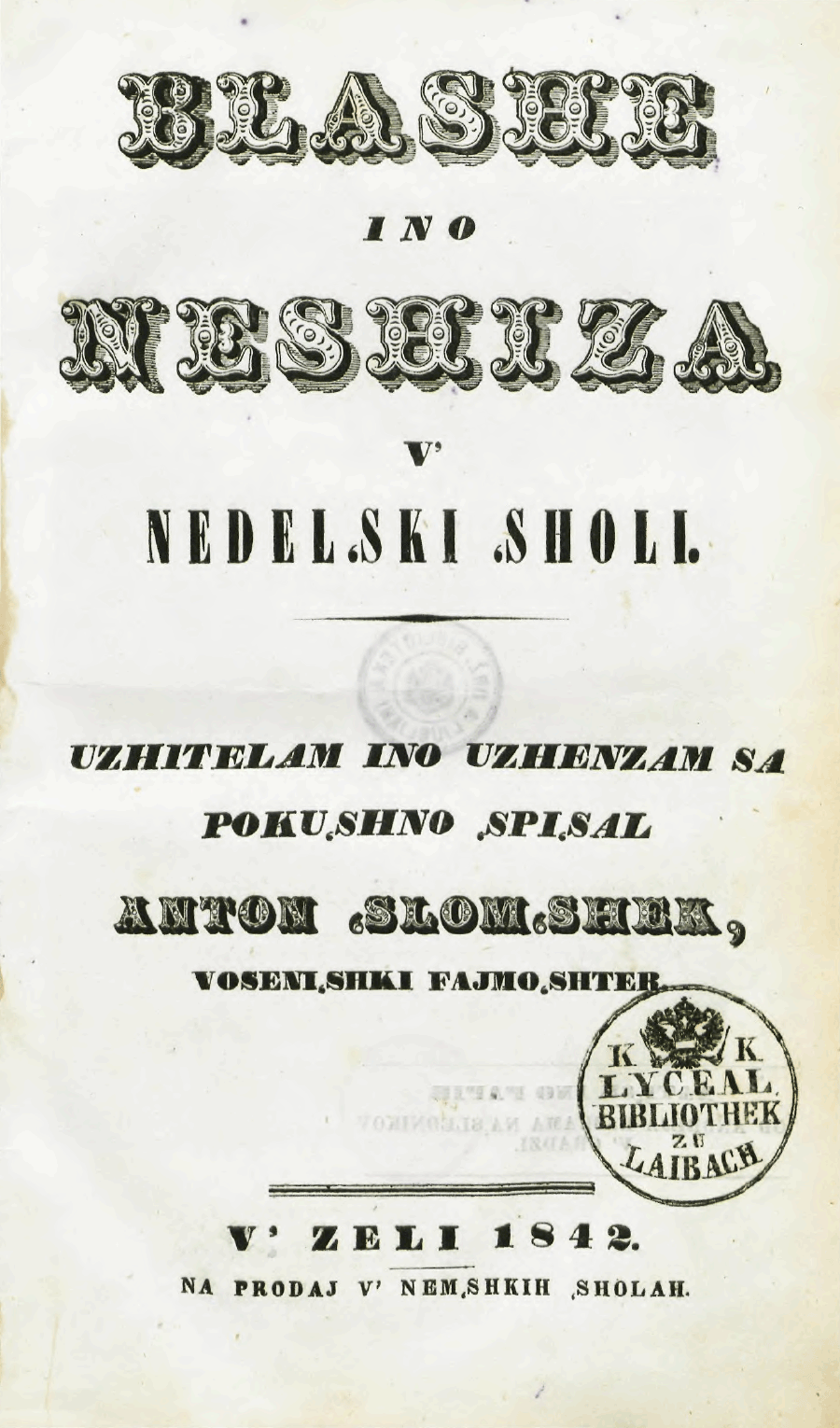

When it became evident that a beginner’s schoolbook was essential, Slomšek prepared and published the school reader, Blaise and little Agnes in Sunday School (Blaže in Nežica v nedelski šoli) in 1842. It was the first school reader in Slovenian language and it was a great success, it was completely sold out by the following year. It was published in ten volumes and contained practical information that a child needs to learn, such as matters of cleanliness, how to put out a fire, how to manage an apple orchard. The school reader was never republished, although it was widely admired and copies were later discovered in Czechoslovakia and Russia.

Slomšek played a key role during the controversy regarding the inclusion of Slovenian language in the state school curriculum. He spoke strongly for the inclusion of Slovenian as a compulsory school subject. Opposition was strong. The main argument seemed to be that Slovenian children speak Slovenian at home and so they already know it. His counter argument was that German children also know German and Italian children know Italian and yet their language is included in the curriculum. There was no further opposition after that. Slovenian language was formally included in the state school curriculum.

Anton Martin Slomšek was appointed as the Bishop of Lavant by Pope Gregory XV1 in 1846. This was a considerable area comprising the two northern Slovenian regions, Styria (Štajerska) and Carinthia (Koroška). In the following years Slomšek used all his influence to gather other Slovenian speakers from the Bishopric of Graz to his authority. He succeeded in moving 200,000 Slovenian speakers to his own pastoral care and the advantages of Slovenian literacy.

In 1846 he began publishing an annual journal, Drobtinice (Crumbs) for his Diocese; the first such journal in Slovenian.

Another great initiative was the establishment of The Brotherhood of St. Cyril and Methodius (Bratovščina sv. Cirila in Metoda), a movement towards greater ecumenism efforts with the Slavs of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

A significant contribution to the development of a literary language was co-founding, with Andrej Einspieler and Anton Janežič the first Slovenian publishing house, Hermagoras Society (Mohorjeva družba) operating from 1852. It has endured into the 21st century, and is still a major publishing company in Slovenia today.

Slomšek had a great interest in Slovenian folk songs. His two anthologies of Styrian and Carinthian songs have been a great contribution to the Slovenian treasury of traditional songs. He composed songs, including songs for children. He is said to have deplored the drinking and singing wine culture of Slovenian countrymen and therefore wanted to provide, also another kind of song. Yet one of his most memorable and charming songs is about a little old man, sitting in his vineyard, somewhere in the gentle hills of Dolenjska (Lower Carniola), in the company of friends thanking the Heavenly Father for one of his great creations, and one more glass of sweet wine.

Slomšek died of stomach ailment on 24 September 1862 in Maribor. A man of great authority, great talents and a great heart, Anton Martin Slomšek understood his people and loved them. He left a permanent legacy for the Slovenian nation that is unparalleled.

Aleksandra L. Ceferin