The architectural legend of Slovenia

Joze Plečnik (1872-1957) holds a special place in the history of the Slovene nation. He became one of the leading architects of central Europe, creating innovative work of originality and brilliance that has outlasted major trends of the period and led to a rediscovery by the post-modernists. He has been referred to as the “Slavic Gaudi” (F.Achleitner), an original genius who “created his own impressionistic legacy – idiosyncratic, hermetic and inimitable” (W.Singer) and given the apt title of “modern classicist” (P.Krecic)

Friedrich Achleitner compared Joze Plečnik to Antonio Gaudi: “Like Gaudi, he inhabits a frontier zone between cultures; he is an ‘architectural fundmentalist’, but also an artisan, a technician, an inventor, and a landmark figure for a newly developed national architecture. In his work, he was always fully conscious of his ethnic group and his region, while remaining critical with respect to ‘popular’ as well as ‘noble’ culture, and even able, through extreme self-control, to integrate emotional phenomena such as kitsch into his field of reference”.

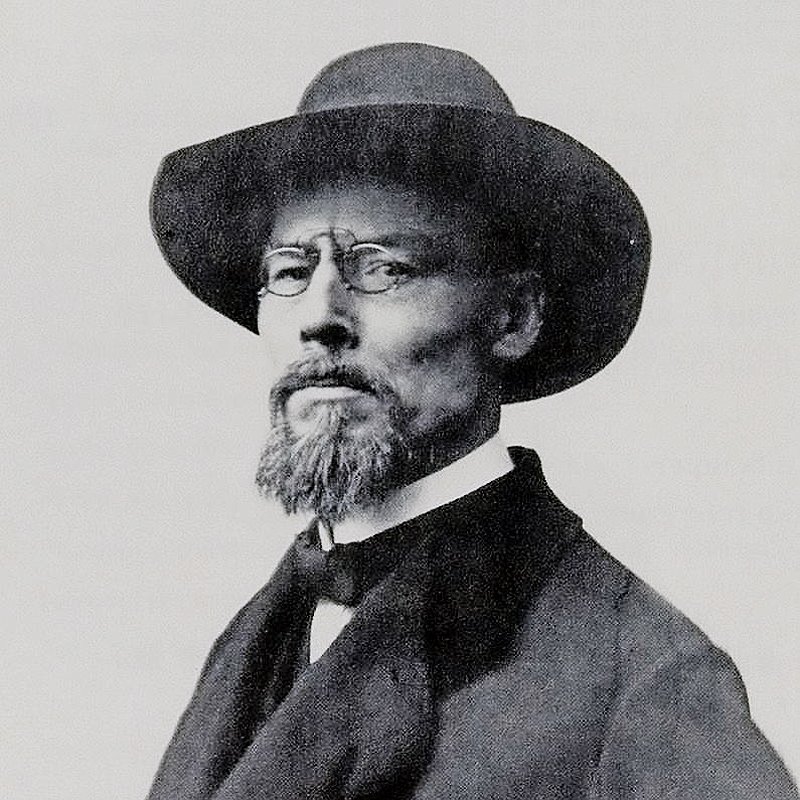

Plečnik 1904, successful architect in Vienna

Peter Krecic, the foremost Plečnik expert in Slovenia today sums up the significance of this great Slovenian architect:

“Plečnik’s contribution to the formation of the national Slovenian ideology of Modernism is substantial, yet it was also European, even international in scope. There is almost no form in his art that springs exclusively from Slovenian vernacular sources. From the end of the 19th century, when the new cultural and political leaders were at the helm of smaller stateless nations, there was a widespread search for national art as a means of achieving cultural legitimacy. Plečnik felt he should contribute to such aims. In his personal artistic programme, he consciously sought inspiration in the classical Slovenian tradition, in the vestiges of antiquity, in the ancient Emona, in the traces of Italian Baroque found in Ljubljana. Indeed his entire vision of Ljubljana as the new Athens was based on his perception of Ancient Rome, of the Italian renaissance and Baroque periods, and the Mediterranean. At the same time he never lost his northern touch, his mystical and mythical self, which he expressed most eloquently in his realisations in wood. This side of Plečnik stems largely from the Viennese Secession and Expressionism, but it also owes much to Slovak and Slovenian rustic tradition.

Thus Plečnik embodies and reconciles two artistic natures, two fundamental artistic moods. The meeting between North and South rightly takes place in Slovenia and particularly in Ljubljana, its capital. Joze Plečnik in synthesizing these traditions, natures and moods, should thus be considered one of the greatest – and possibly one of the last – universal artists.”

Debra Schafter defined Plečnik’s work in terms of the Postmodernist movement and present day viewpoint:

“Plečnik’s pluralistic and inventive vocabulary juxtaposes tradition with innovation in a manner we come to associate with the postmodern attempts to collapse styles through a process of appropriation and divestiture. Indeed, like the architects of the modern era, Plečnik did not use historical references ‘naturally’ that are to establish his monuments as a part of some immediately recognizable tradition, but ‘critically’, as a means to revitalize forms through new and unexpected references. Plečnik reorganized traditional codes according to new paradigms that could allow modern concepts regarding structure, function, space and viewer to take place in a vast cultural, historical and architectural heritage.”

The heart of Plečnik’s Ljubljana:

the river, the three bridges, the people

Plečnik was born in Ljubljana, the son of a Slovenian cabinet-maker, and was to follow in his father’s trade and never thought of becoming an architect. However his talent for drawing was recognized early, when he received a scholarship at the newly opened vocational school for industrial arts and crafts in Graz, Austria. It was the first step toward the architectural profession. Here he met his first true master, the architect Theyer, who befriended him and made him his assistant. With Theyer’s help Plečnik moved to Vienna, where for two years he designed furniture and supervised production for a large furniture company. He tried unsuccessfully to enroll at the School of Decorative Arts and frequented museums, galleries and exhibitions.

The decisive moment in Plečnik’s life occurred, when he saw at an exhibition Otto Wagner’s plans for the new cathedral in Berlin. When he became Wagner’s student, he was on his way towards an extraordinary career.

As architect Plečnik was a visionary and a reformer. He was a pioneer in urban planning, an innovator in the use of new building materials and their potential for attempting new structural and ornamental building solutions. While highly original, experimental and individualistic in his building designs, he simultaneously sought to incorporate the historical dimension and achieve a continuity of established traditions.

During his career he created architectural masterpieces, leaving his stamp on three central European capitals – Vienna, Prague and Ljubljana. They represent three distinct stages in the development of his genius. In each city he rose to new challenges and created monumental buildings, which amazed his contemporaries and are still astonishing today.

In Vienna (1894-1911) Plečnik completed his studies and made his mark as one of the most exciting and accomplished secessionist architects and designers of the time. His Zacherl Palace (1905) established his reputation as an original, innovative and brilliant architect – and a foremost exponent of expressionism.

Prague (1911-1920) became the arena of Plečnik’s most ambitious and monumental building project, the restoration of Hradcani; the ancient and massive castle fortress of Prague. He was appointed The Castle Architect, given the brief by the President Stefan Masaryk to create a powerful symbol for the newly emerged Czech nation-state. The project took 15 years to complete (1920-1935) and was not only the most monumental but also the most challenging undertaking of his professional life. The Prague Castle is a colossal monument to Plečnik’s philosophy of art, a brilliant example of combining tradition and modernity, and an enduring symbol of Czech nationhood.

While residing in Prague, Plečnik began regularly to visit his native country, discovering Slovenian architectural traditions, particularly the Karst region.

Ljubljana (1920-1957+) began to draw him. It was the city where he truly felt at home. In 1920 he accepted a professorship in Ljubljana in preference to a number of such positions offered to him. He was fifty and at the beginning of the most mature and fertile period of his life.

In 1918, when World War I ended, the Austro-Hungarian Empire broke into a number of nation-states. Slovenia became part of the Kingdom of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. German cultural and political dominance over Slovenia ended. There was a tremendous upsurge in all the fields of endeavour for Slovenes, a time for national self-assertion. Plečnik was able to start work on the most astounding and enduring legacy of his life’s work. His native city Ljubljana, the cultural and political centre of Slovenia, became the arena for his deepest desire: to create as an architect and as a Slovene a worthy capital for the Slovenian nation.

Plečnik believed that architecture had an important role in the life of the individual, the society and the nation. He saw the need to educate young architects to an awareness of the social role of architecture. A pedagogue at heart, his influence is still felt in Prague. In Ljubljana the school of architecture that he founded is still thriving on the Plečnik legacy and has produced generations of exceptional architects. It has been said, that he would have done the same for The Vienna School of Architecture, given the opportunity. Certainly Otto Wagner thought so, with unanimous support of colleagues and students.

In Slovenia Plečnik had the opportunity, rarely given to a master architect, for the urban development of a city. He fulfilled it beyond expectations. The legacy he left to his country has come to be known as – Plečnik’s Ljubljana. With his designs, plans and landscaping he breathed beauty and style into the city core, covering the areas of the Ljubljana castle, old and new sectors of the city, embankments of the river, parks and squares throughout the city.

The course of Ljubljanica River was a project on its own, with redesigned and rebuilt bridges, new embankments along the river and landscaping. There were numerous special projects – the city squares and parks, which were given a new stylish appearance: the Tivoli Park, the Congress Square with Park Zvezda, Tromostovje (The Three Bridges) and the Market. A number of Plečnik’s buildings are Ljubljana’s major landmarks: The National and University Library, The Church of St.Francis in Siska, Zale, The Church of St.Michael on Barje, The Baraga Seminary, and The Ljubljana Stadium.

During the decades following the end of World War 2 Plečnik was regarded as old-fashioned and outmoded, his role as Head of School of Architecture sidelined. However, he continued to work till his death, and the socialist regime on the whole honoured the old master. Then came the seventies and rediscovery of Plečnik’s genius by the post-modernists with their search for historical forms and “the lost wisdom” of architecture. It was a path on which Plečnik had preceded them, finding interesting and exciting solutions. Plečnik, the “modern Classicist”, presented them with buildings exemplifying the juxtaposition and tension between the tradition and innovation. Plečnik’s Ljubljana was an outstanding example of the modern urban vision and creative ethics – a city that preserved in its older structure important stylistic predecessors – the ancient Roman Emona, the Mediaeval town, the Baroque town, the 19th century town.

Plečnik’s work received high acclaim in 1986, with the great retrospective exhibition at the George Pompidou Centre in Paris. The exhibition was first taken to Ljubljana, where it had extraordinary success, then to Madrid, Munich, Karlsruhe, Milan, Venice, New York and Washington. In USA he was the first Slovenian artist to create such an impact. Subsequently the Paris exhibition became the foundation of a permanent exhibition of Plečnik’s work in the Fuzine Castle in Ljubljana.

Plečnik was a great artist and a visionary. He was also a great Slovenian patriot. Plečnik’s Ljubljana is a monument to a man’s love for his country and pride in his Slovenian heritage. We can say today that he lived up to the words he wrote in a letter to his brother on completing his first major project, the Zacherl Palace in Vienna. He hoped for success “for the sake of Slovenia”. At a time when it was not politically correct to be a Slovene, he demonstrated with his achievements and pride in his Slovenian identity that a small nation can achieve greatness. That it is the quality of its people that counts and not the strength of numbers.

Jože Plečnik in Prague (1911-1920)

The Castle Architect – Monument to Czech Nationhood

After arriving in Prague, Plečnik was appointed to a teaching position at the Prague School of Applied Arts. For the first time he received a regular salary, had the benefit of university vacations and was able to devote more time to his present interest – the studies of Slavic art.

Hradcani, Presidential Residence designed by Plečnik

On his retirement, he replaced Jan Kotera as the Head of the School of Applied Arts, and in the words of Paval Janak reoriented the school’s revolutionary modernity toward a “mature modern classicism”.

Plečnik was an inspiring teacher, successfully blending in his approach, classic and modern pedagogic principles:

“The important thing is not who is guiding the student. A master has but one obligation: to help his student to learn, to see and to discover…”

In 1914 Plečnik, along with Kotera, Gocar and Kamil Hilbert, was among the founders of Spolecnost Architectu, an association of architects opposed to the official academicism of Czech architecture. The works produced at the school and published at the end of 1912 in Spolecnost Architectu journal are an interesting mixture of the classical (in the style of Plečnik), the patriotic (focusing on the nationalist theme) and of cubism (representing the avant-garde).

During the war years Plečnik could not expect any important commissions during this time. He turned his attention to decorative arts, and involved himself in the craft of gold- and silversmith. He travelled extensively in Slovenia, particularly the Karst region, and for the first time became thoroughly acquainted with the art of his country. He grew concerned that the lack of sensitivity of foreign architects was causing Ljubljana to lose its character, acquired over the centuries from proximity to Italy, and began reflecting on the capital’s city planning problems. It was period of maturation for Plečnik, giving way to an intense desire to return permanently to Slovenia.

The end of World War I (1914- 1918) saw the breaking up of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the emergence of new nation-states – Czechoslovakia, Hungary and The Kingdom of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (later renamed Yugoslavia). Proud of their nationhood, the new states were anxious to start reconstruction with great buildings and the establishment of schools of architecture. Plečnik, by then an architect of considerable renown, was offered professorships in Prague, Ljubljana, Belgrade, Berlin and Zagreb.

Before he made up his mind, a new challenging offer caused him to delay his decision. Tomas G. Masaryk, President of the Czech republic was addressing the problems of urban development in the capital and the long overdue restoration of the Prague castle. He wanted the castle with its rich historical tradition to become the national symbol of the young republic.

Plečnik was first appointed as a member of the jury for the competition, chosen for his plan of Garden of Paradise and finally appointed the Castle Architect with the brief of restoring the ancient fortress.

Masaryk was looking for an inspired creator whose architectural design could express the very values on which the Czech state was based. Prague had become the capital of the newly established Czechoslovak republic and needed a striking monument as centrepoint and expression of its newly founded nationhood.

Tomas Masaryk saw in Plečnik the visionary genius with skill and ideas to realize the concept. He noted in his 1925 declaration:

“The nation regards the castle as a national monument, hence we must transform a castle intended for the monarch into a democratic castle.”

He understood and shared Plečnik’s ideas of blending the classical with the modern, and drawing on ancient tradition as expression of national identity.

Plečnik’s work on the Prague Castle – Hradcani was a watershed and the most monumental architectural project of Plečnik’s career. None of Plečnik’s creations can compare in importance and breadth to the restoration of Prague Castle. He shaped Hradcani into the great national monument of the Czech state. He did away with centuries of accumulated additions, removed restricting walls, opened stunning vistas onto the city, laid magnificent gardens, designed monumental staircases and gateways, remodeled the President’s residence and filled the place with national symbols.

The work was monumental in conception and scope, and intensely satisfying to Plečnik. However his restoration work was too drastic and innovative to be understood or appreciated by the general public and he had to withstand constant attacks in the media.

His work on Hradcani occupied him for 15 years (1920-1935). He moved to Ljubljana in 1920, but returned to Prague each year during the vacations, working with zest and enthusiasm. The Prague Castle remains an enduring and extraordinary monument to Czech nationhood and Plečnik’s genius.

Joze Plečnik in Ljubljana (1920-1957+)

“A world urban-planning phenomenon”

Plečnik’s arrival in Ljubljana in 1920 inaugurated the third significant period of his career. He was now 50, at the peak of his mature powers and approaching the most fertile period of his life. The decision to settle permanently in Ljubljana gave direction to the rest of his life and led to his greatest achievement. Very few artists have the chance to design large urban areas, much less an entire city. Plečnik was fortunate in that. Critics have referred to Plečnik’s inventiveness, originality and personal style and described Ljubljana as the city that bears “the artistic stamp of one master, signed by the artist.”

Peter Krecic, the director of Ljubljana Architectural Museum and author of several monographs on Plečnik has described Plečnik’s urban planning work in Ljubljana as “a world urban-planning phenomenon”.

In Ljubljana Plečnik succeeded in two chief aims: to found a Slovenian architectural school, and to make Ljubljana into a Slovenian Athens and a worthy capital of the nation.

He succeeded in both aims beyond expectations.

He was appointed Head of the Technical School in Ljubljana. A pedagogue at heart, he was able to satisfy his need to teach to the full. His development as architect is linked to his development as teacher, and even today continues its pedagogical mission. The Ljubljana School of Architecture has produced many architects of note.

He also succeeded in creating a beautiful, liveable capital city for Slovenes. One cannot fully understand Plečnik and particularly his mature work, without his Slovenian background, which played a major role in his development as architect. His search for historical forms also meant searching for traditions within his Slovenian culture. His architectural mission in “making Ljubljana a worthy capital of Slovenia” was an essential part of Plečnik and the foundation for his urban planning work.

Ljubljana is the city where the synthesis between the North (German) and the South (Roman) is most originally expressed. Plečnik’s nostalgia for Ljubljana after his discovery of Karstian art and architecture deepened. The study of local architecture drew him closer to the baroque tradition. He was attracted to 18th century, a period when artistic influence of Venice was the key to central Slovenia. The fascinating accumulation of influences and layers, as well as the Byzantine architecture of Yugoslavia became the sources of his inspitration.

The first major project that inaugurated Plečnik’s plans for Ljubljana, was the Church of St.Francis in Siska (1925-1927). With this grandiose and astonishing building, the architect introduced into Ljubljana a new set of dimensions and a new standard of building on a grand scale. It amazed the city and created some resistance. It also started the most extraordinary and fertile period of creativity and realization of plans. It was the beginning of the “urban planning phenomenon” that is Plečnik’s Ljubljana.

From 1920 onwards, while occupied with work on the Prague Castle, Plečnik designed and built a staggering number of building projects both within and outside Ljubljana, planned parks and beautiful city spaces. The work on Ljubljanica embankments was started in 1931 and completed with some interruptions in 1939, Tromostovje (The Three Bridges) berween 1930 and 1932.

An integral part of reconstruction was “green architecture”, with weeping willows representing cupolas, poplars representing columns, hedges are walls, the fresh greenery enhancing and defining the gently curving waterway within its deepened riverbed and high embankments. Plečnik gave the river a series of features, enhancing its function as an essential artery of city life: through bridges, which give access and character, through the development of the Trznica (market) along its bank, and the wonderful Tromostovje (The Three Bridges) in the very heart of the city.

Plečnik’s plans for the National and University Library were completed by 1931. The work began only in 1936 due to wrangling with Belgrade about finances. Completed just before the beginning of World War II, it is the central project of Plečnik’s opus in Slovenia, and reputedly one of the finest achievements of his artistic maturity. It is conceived symbolically as a temple of knowledge. Its long colonnaded entryway portrays the journey from the darkness of ignorance into the light of knowledge.

Except for periods of serious disruption and even terror, Plečnik continued working during the war, designing and planning everything from monumental plans, such as Ljubljana Castle to smallest details, building onto his enormous opus of realized and unrealized projects.

Plečnik’s legacy is a city centre shaped with pavements, copses, statues, columns and a number of unique buildings, embankments parks and riverscapes. The National and University Library, Plečnik’s Market, The Three Bridges, have lent character, distinction and beauty to the city centre.

Among the many buildings and areas designed and built by Plečnik in Ljubljana are: The Chamber of Commerce, Craft and Industry (1925-1927), Ljubljana Stadium (1925-1935), Mutual Assurance Building ((1928-1930), Krizanke (1941), Congress Square (1927-1941), Tivoli Park (1929-1934), Baraga Seminary (1938-1941), Ursuline Gymnasium (1939-1941).

At the centre of Ljubljana is the Tromostovje, connecting the old city and the new, its living heartbeat. The whole areas along the river Ljubljanica embankment, the city squares, the bridges, the Tivoli Park and the streets leading outwards were gradually restored and embellished with new pavements, single trees and plantations, columns, lamps, monuments, bridges and embankments, gradually creating wonderful living and strolling spaces.

Plečnik was interested in creating social and sociable spaces, spaces for the people, such as churches and markets, and to make them pleasant as well as aesthetically pleasing. It is a strong part of Slovenian culture to honour their departed and make their final resting place beautiful with memorial stones and flowers. Plečnik created the beautiful Garden of all Saints, which became known as Žale (the place of mourning). It is a serene and beautiful place, consisting of administrative premises, two storeyed and colonnaded, the composition divided by the ceremonial portal in the centre. In the axis of the portal is the platform for the speaker, to the left and right are the 14 chapels, apparently random, in a variety of architectural styles, from prehistoric tumuli, classical temples and Serbian medieval architecture to entirely modern. The hedge of high shrubs and other ornamental plants create a living, rich, ceremonial ambience. The place for final parting in his view had to be a ceremonial, almost ritual space, a place of consolation and Christian hope rather than sorrow and despair “a classical garden, a garden with emancipated, absolute architecture”. (Krecic)

Plečnik wanted to retain the historically multi-layered Ljubljana with its Roman, Medieval and Baroque periods and planned accordingly. He restored the past and added his own creations, imbuing the cityscape with his own perception of pleasant city living.

The present-day Ljubljana gives expression to what is alive, enduring and beautiful, blending the traditional forms and the new; the stone sculptures and the living trees; the bridges and the flowing river; the many-layered past and the modern present – a historicist’s perception of time and history, combined with the organic perception of architecture and art as expressed in building.

Aleksandra Ceferin, Thezaurus 2002

My thanks to Dr. Peter Krecic, the Director of the Architectural Museum of Ljubljana for advice, contribution towards preparation of the Plečnik articles, and the permission to use the photographic material in his publications.

Sources: Peter Krecic, Joze Plečnik, DZS, 1992

Peter Krecic, Joze Plečnik – Branje oblik, DZS, 1997

Peter Krecic, Plečnik’s Ljubljana, CZ, 1991

F Burkhardt, C Eveno, B Podrecca, (ed.): Joze Plečnik, Architect: 1872-1957, MIT Press, 1989

Slovene Studies, Journal of the Society for Slovene Studies, No.2 1996

Aleksandra Ceferin, Thezaurus 2002

My thanks to Dr. Peter Krecic, the Director of the Architectural Museum of Ljubljana for advice, contribution towards preparation of the Plečnik articles, and the permission to use the photographic material in his publications.

S ources: Peter Krecic, Joze Plečnik, DZS, 1992

Peter Krecic, Joze Plečnik – Branje oblik, DZS, 1997

Peter Krecic, Plečnik’s Ljubljana, CZ, 1991

F Burkhardt, C Eveno, B Podrecca, (ed.): Joze Plečnik, Architect: 1872-1957, MIT Press, 1989

Slovene Studies, Journal of the Society for Slovene Studies, No.2 1996