Language and Literacy – Politics of Religion in Middle Ages Glagolitic script came into being during the 9th century. It was invented to accommodate the complex sound system of the old Slavic language for the purpose of spreading Christianity among the Slavs. From a beginning in Macedonia, the glagolica and its Christian message spread like wildfire over Bulgaria, Croatia, Slovenia, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Ukraine and Russia, that is, over the whole Slav world.

Glagolitic script came into being during the 9th century. It was invented to accommodate the complex sound system of the old Slavic language for the purpose of spreading Christianity among the Slavs. From a beginning in Macedonia, the glagolica and its Christian message spread like wildfire over Bulgaria, Croatia, Slovenia, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Ukraine and Russia, that is, over the whole Slav world.

Having made its mark, glagolica continued in use in Slavic church services in some cases into the 20th century. However, by the 10th century a simpler script was introduced – the Cyrillic script or “cirilica” – which is to this day the official script of Russia, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia. It was named Cyrillic in honour of St.Cyril who was thought to have invented it. While glagolica continued in use particularly in Croatia into the 20th century, Latin script was gradually adopted by the western Slavs – Slovenes, Croats, Czechs, Slovaks and Poles – who came under the sphere of influence of the Roman Catholic Church and Western European political sphere. Russians, Serbs, Macedonians, Bulgarians came under the influence of the Byzantine empire, established the Orthodox rite and retained Cyrillic script in religious as well as secular sphere.

For all the Slavs the common legacy bequeathed them by St.Cyril and Methodius was the right to celebrate Mass and conduct all church services in their own tongue, while the rest of the world retained the Latin services until the Vatican II.

The story of how it all came about makes a fascinating tale. It began with a request to the Byzantine emperor for Christian missionaries who spoke the Slavic language. The request came from Moravian Prince Rastislav and it was a move principally dictated by political necessities. Rastislav wished to reduce the political power of German priesthood, which they exercised by virtue of control over the new religion. Through German priests German princes were able to wield the influence, which came with the authority and sanction of the church. Prince Rastislav sought the assistance of the other great power of the time – the Byzantine Empire to provide the counterbalance and support for his own rule.

The history books tell us that the emperor promptly acceded to the request. Two exceptionally able brothers Constantine (later known as Cyril) and Methodius were asked to undertake the task. We know that they had already undertaken an important and successful mission to Khazars and that they were fluent speakers of their native Macedonian and that Constantine was a learned man, a linguist, who had been given the honorary title Philosopher.

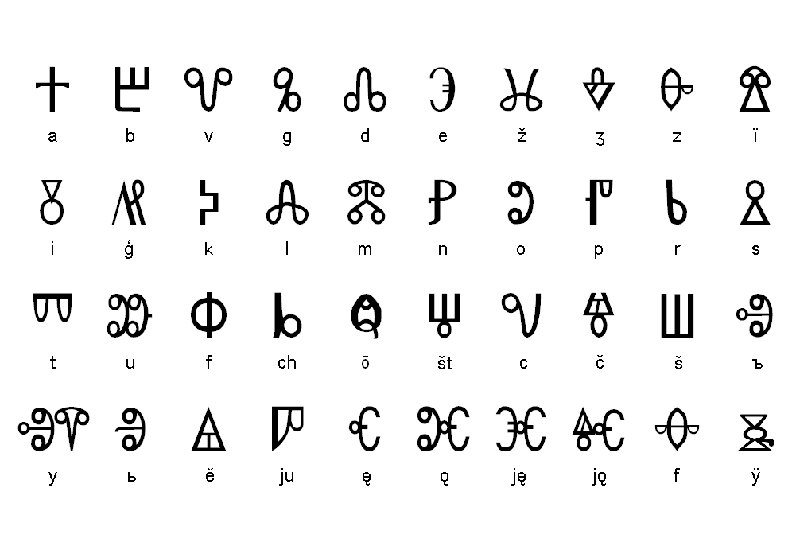

As part of preparation for their task, they wanted to translate a number of essential religious texts into Slavic. Constantine found the Greek alphabet unsuitable, since it lacked many of the Slavic sounds and consonantal groups. So he set out to invent a new Slavic alphabet. With a background of knowledge of scripts current in Asia and Africa at the time, he was able to construct an alphabet which was precise and complex and included all the sounds specific to Slavic tongue, for instance the nasal O and E, the reduced vowel, consonantal groups št and žd, etc, with as many letters as there were sounds distinguishing words for their meanings.

Constantine named the script glagolica, meaning speech. Since the word Slav also means speaker, the name was appropriate and significant, reminding the user that here was a tool of communication and empowerment. In its conception and as a linguistic tool, glagolitic script was an amazing achievement – a tool to give power of the written word to half the Europe. It was also a powerful demonstration of the effective use of the native language in spreading a new religion and a new concept of the world.

Constantine proceeded to translate selections of Gospels, Acts of Apostles and liturgical texts. These are the oldest texts in a Slavic language.

(The Freising Manuscripts / Brižinski rokopisi in Latin script, were written about this time but were only known from 10th century copies and were also limited to a few texts.)

The language – the Macedonian variant of the 9th century Slavic – became known as Old Church Slavic. It did not vary much from the Slavic spoken in the north. In time words used exclusively in the north were added, for instance the word for cross – križ, which is still used in Slovenian today. Together with translations that followed the initial ones, this language was retained in the liturgy of the Orthodox Churches of the southern and eastern Slavs, and continued in use also in Croatia and in Ukrainian Roman Catholic Church of the Eastern rite.

By 863 the brothers were ready and started on their slow journey to Moravia, stopping to teach on the way. Their journey took them through Bulgaria, Serbia, and drew them into a power struggle that they did not want. The less successful German priesthood, which insisted on the use of Latin in the church ritual, reported them to the pope, for their “heretic” use of Slavic language in the celebration of the Mass. So they traveled to Rome and defended their use of the vernacular in church liturgy. They did this so successfully that they won pope’s approval. St.Cyril entered the church and died in Rome in 869. Methodius could not return to Moravia, because of the political situation there. He was asked by Slovenian Prince Kocel to work in Pannonia. Kocel supported his consecration as Bishop, and welcomed the edge this gave him in breaking the power of the Salzburg hierarchy over his land. So Methodius was consecrated bishop of Simium, with authority over Serbs, Croats, Slovenes and Moravians.

The German bishops did not rest in their attempts to get rid of “this turbulent priest”, accused him of infringing on their power and imprisoned him. He was released only after German defeat in Moravia and pope’s intervention. However, to appease Germans, Methodius was no longer permitted to celebrate the Slavic Mass. In 879 he was again summoned to Rome to answer German charges that he had disobeyed the restriction. Methodius was again given a chance to explain to the Pope, how important was to celebrate church rites in the language that people understood. The result was, that the Pope gave him permission to use Slavic tongue for the Mass, Scripture reading and the Offices. He was also made Head of the hierarchy in Moravia. Methodius continued his work and it is said that he translated most of the bible and the works of Church Fathers before his death in 884.

In the Slavic world St. Cyril and Methodius became legend, revered as the Apostles of the Slavs. They were great teachers, who brought to the Slav peoples, together with Christianity and a new concept of the world, the written word, a pride in their own tongue and an awareness of themselves, their language and their identity, separate from the Latin based tradition of the Western Europe. This act was to divide Europe initially into Eastern Byzantine and Western Roman both in professed religion and in political allegiance. It split the Slavs themselves into those who established the Orthodox national churches and those who looked to Rome as the supreme religious authority. In the 20th century that thousand year old division split Europe once again into western democratic and eastern communist political systems. From such divisions came conflicts and cross-fertilizing of ideas, which still characterize the Europe of today and gives its special rich tapestry of the present, flowing from a turbulent and energetic past.