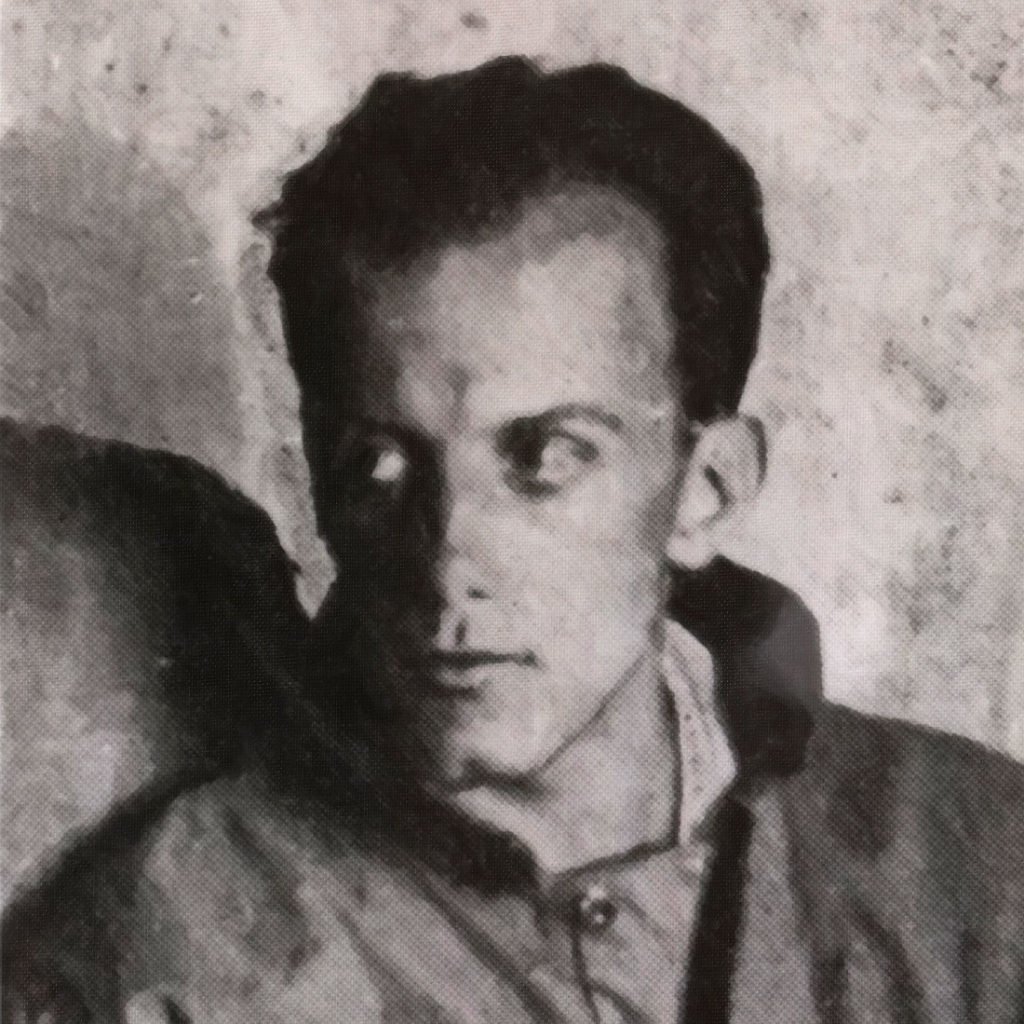

Slovenian writer Vladimir Bartol (1903-1967) published his novel Alamut in 1938. Set in northwestern Persia of 1092, it was intended to be a metaphor for Europe of his own time, providing insight into the rise of formidable leaders Mussolini and Hitler. The novel was received with great interest and critical attention in Slovenia. In the following decades Alamut was discovered by an increasingly broader reading public and translated over time into 19 languages. Its theme of power and insight into charismatic leaders and ideologues continues to resonate in the 21st century. Vladimir Bartol has succeeded in attaining the unique distinction among Slovenian writers as the author of the most translated Slovenian novel and an international best seller, highlighting the Slovenian novel in the global landscape of literature.

Bartol notes in his Memoirs 18 years after the publication of Alamut, that the concept for the novel originated in 1927, in an encounter with Slovenian literary critic and essayist Josip Vidmar in Paris, while studying at the Sorbonne. Vidmar drew his attention to an episode in The Travels of Marco Polo. It concerned a powerful local warlord Hasan ibn Sabbah who lived in Persia around 1092. He trained promising young men to become fanatical warriors, bound to him by the use of hashish and an experience of paradise, a wondrous garden with beautiful maidens. The young men were then sent out on dangerous, often suicidal missions.

The fortress Alamut is the Thousand and One Night setting for the novel. Bartol began writing after an intensive study of 11th century Iran. He records in his Memoirs that »he wrote with the rigour and devotion of a chronicler, who notes only what he truly witnesses and experiences«. His expressed intention is »to reveal a great, as exact as possible, and as realistic a picture of a particular historical course of events and a specific historical individual«.

He speaks further of the »melding of the two periods in his consciousness, Persia of 1092 and Europe of 1938. That is to say, while portraying the charismatic leader Hasan ibn Sabbah, he is also reflecting on the two powerful leaders of his time, Mussolini and Hitler. Bartol is aware of the complexity of his undertaking and ponders in his Memoirs whether his novel might possibly represent a new genre. He concludes that it should be after all regarded as a historical novel, since it is written with great attention to historical detail. He adds that »it is over and above that also a psychological, ideological or philosophical novel, and possibly a myth«.

The author followed the path of his novel among the reading public of Slovenia and later of Yugoslavia. In 1946 Alamut was published in the Czech language, in 1954 in Serbian. The first Slovenian edition of Alamut had been sold out and was re-published in 1958 with 20,000 copies. In the 1960ies, the period of Balkan turmoil, Alamut became »a cult favourite« throughout Tito’s Yugoslavia.

We read in Bartol’s Memoir about periods of special interest in the novel: »Alamut exploded in the course of its existence three times: the first time at its publication in 1938, the second time one year later at the launching of the book by Francois Pons, French ambassador in Germany, that included an account of his visit at Hitler’s retreat at Berchtesgaden and Rauschnig’s Conversations with Hitler; and the third time in 1956, after the portentous speech by Khrushchev at the Congress of 24th February in Moscow.

Such periods of renewed popularity continued after Bartol’s death in 1967. Alamut reached a new milestone in 1988, when the novel was published in French. It became a bestseller in France, and more translations followed. It was a period of social and political change in eastern Europe, the time of glasnost and perestroika. Alamut was published in Spanish (1989), Italian (1989), German (1992), Persian (1995), followed by Arabic, Greek, Korean and Slovak.

Vladimir Bartol did not live to witness the full success of his novel as a metaphor for political trends into the 21st century. The terrorist attacks of 2001 excited a fresh wave of interest. Alamut was published in Hebrew (2003), English (2004), Hungarian (2005) followed by Finnish (2008), Turkish (2010), Macedonian (2014), Lithuanian (2014), and Bulgarian (2017).

Such was the novel’s appeal that it became the inspiration for the Assassin’s Creed series of video games. Many elements of the book’s plot can be found in the first game, as well as the motto “nothing is true; everything is permitted” as the guiding principle of the Order of Assassins, who feature as the descendants of the Ismaili.

In the incisive afterword to his English translation of Alamut in 2004 Michael Biggins advises the reader to read Alamut first as a historical novel, since it offers unique insight into Persia of 1092. »A second reading will then open the pathway into the multi-layered literary masterpiece that is Alamut, when it can be truly appreciated as a composite portrait of Mussolini, Hitler and Stalin, the ruthless charismatic leaders of the 20th century«.

The author has headed his novel with two mottos. The first is Hasan’s motto:

»nothing is true, everything is permitted »

The second motto in larger print is a warning and a counterpoint:

OMNIA IN NUMERO ET MENSURA – everything within reason and its proper measure.

The first motto is the licence to rule unconditionally, the second a warning not to overstep the bounds of what is appropriate and reasonable.

Vladimir Bartol wrote a commentary on Alamut for his 1958 edition, which is illuminating:

»No matter how terrible, inhuman and despicable the methods are that Hasan uses, the people subject to him never lose their most noble human values. The sense of solidarity among the fedayeen never dies and friendship flourishes among them, just as it does among the girls in the gardens. Ibn Tahir and his comrades are eager to know the truth and when he finds out that he has been deceived by the man he had most trusted and believed in, he is no less shaken, than when he learns that Miriam’s love for him was a deception. And finally in all his grim knowledge Hasan is unhappy and alone in the universe. And if somebody wanted to find out from the author what he meant by writing Alamut, what his underlying feeling was as he went through the process of writing it, I’d tell him:

»Friend! Brother! Let me ask you, is there anything that makes a person braver than friendship? Is there anything more touching than love? And is there anything more exalted than the truth?«

A great deal has been written about Bartol’s novel. Interpretations and relevance to the events and trends of our times abound, however, to quote M. Biggins, they »miss the fundamental fact that Alamut is a work of literature, and that as such its chief job is not to convey facts and arguments in a linear way, but to do what only literature can do: provide intentive readers, in a tapestry as complex and ambiguous as life itself, with the means of discovering deeper and more universal truths about humanity, about how we conceive of ourselves and the world, and how our conceptions shape the world around us, essentially, to know ourselves«.

Aleksandra L. Ceferin