Humanism, reformation, uprisings, wars and plagues Turkish empire’s push into Europe

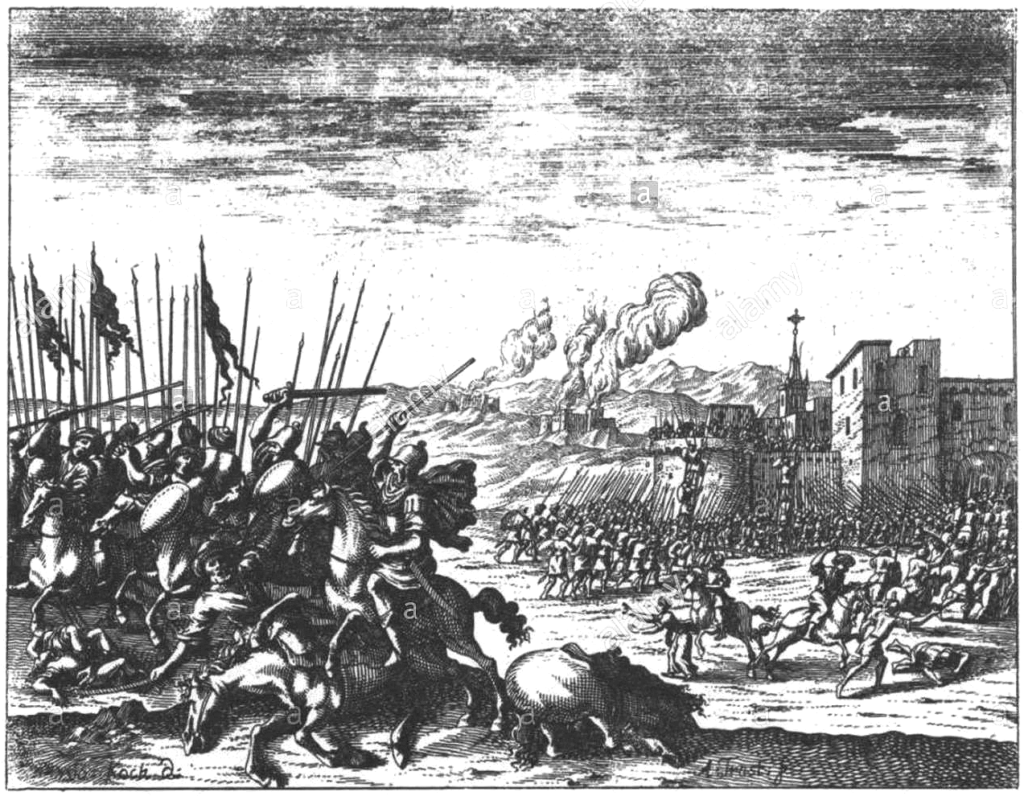

The first Turkish incursions into the territory of Austro-Hungarian lands began in the 15th century, with plunder as the main aim. They lasted 150 years and brought untold suffering above all to the country people. The long range strategic aim was to exhaust Croatian and Slovenian territories to such an extent, that they would offer little resistance to the Ottoman army in their drive for expansion into Europe.

The first great waves of incursions into Slovenian lands occurred in 1408 and 1411. They were repeated in the period 1469 to 1483. The records tell us that in 1471 all the major Slovenian monasteries – Stična, Pleterje, Jurklošter, several suburban churches of Ljubljana and altogether 64 churches – were destroyed, 15,000 captives were taken away, 200 villages and 5 towns burnt. In the wake of the war of 1599 with the Republic of Venice, 132 villages were completely destroyed.

In the 16th century the rule of Sulejman II initiated a new era of attempts at conquest. Between 1520 to 1540 the Turkish border was moved 400km from Belgrade to Budim. It was a strategic move intended to expand Turkish empire to central Europe. In the years 1529 to 1530 Sulejman intended to conquer eastern Hapsburg empire, take Vienna and achieve mastery of all central Europe. This aim was expressed in forceful Turkish incursions on Croatia and Slovenia after 1526. These were not as destructive and expansive as the earlier ones, and aimed mainly to subdue the population in preparation for the main drive towards the conquest of Vienna.

In the second part of 16th century the situation in Kranjska (Carniola) eased, however the population lived in constant fear. This time the attacks came from the east, and it was the population of Prekmurje in north-eastern Slovenia that suffered.

During the two centuries of Turkish incursions the most vulnerable were the rural populations, and they began to organize their own defences. They gradually fortified their market towns, which were raised in status to cities – Kočevje, Višnja gora, Krško, Lož. So the townspeople and feudal lords were able to find protection behind the fortified walls. The country people by their own initiative built “tabors”, fortified places in well defensible high locations. Altogether 350 tabors in Slovenian territories were built. Some of them were quite large, with several watch towers, with space for as many as 2,000 people. Villagers also organized outlooks and a warning system of burning wood-piles on hill-tops (grmade), so they had time to escape to the forest or later behind fortifications.

Turkish incursions during 15th century caused a great deal of material damage and also considerably diminished the size of population. The defence army was formed. In Slovenian territories 28,000 were conscripted from inner Austrian-Slovenian lands – Štajerska (Styria), Koroška (Carinthia) and Kranjska (Carniola). The crucial question of 15th and 16 centuries was, whether the Slovenian space would remain western Christian. The pressure was enormous, and the inhabitants of these lands needed to be persuaded to contribute able-bodied men for the army and building fortifications. Later Slovenian lands were required to carry the costs of major fortifications in Croatia, which became a military defensive zone.

The age of plague, famine and peasant uprisings

The so-called black death epidemic raged in Slovenian territories particularly in the 14th century. From 1500 to 1700 its attacks were strong enough to seriously diminish the size of population. The epidemic came from the east, from the south, from the north in various degree of virulence and devastation. It was spread through trade routes and commercial activities, and struck mainly the towns and cities.

Till the 16th century the plague raged with small intervals over all of the Slovenian territory. It came first from the east, from Turkey and Hungary, after that from the north, striking mainly Štajerska, Primorska and Carniola was invaded by from the south.

The last great epidemic took place in 1712-1715, then it slowly disappeared, due to various preventive strategies to prevent infection, quarantine, investigation of all travellers, the ban of congregation even in churches, closing the gates of towns, prevention of movement within the towns and outside, etc.

The horror of the plague was aggravated by powerful earthquakes, the first and most damaging in 1511. The majority of towns were badly damaged, and a great number of strategically important castles, among them Turjak, Planina, Polhov Gradec, Gotnik, Bled, Tolmin.

It was also time when peasantry was increasingly exploited by the feudal masters, increasing far beyond determined obligations for produce, coin and work. The injustices and exploitation became so unbearable that the peasants of Croatian and Slovenia rebelled and rose in arms against their masters. The greatest revolts were in Koroška (Carinthia) in 1478, in Slovenia in 1515, in Slovenia and Croatia in 1573, in Slovenia in 1635. In Slovenian territories there were from 15th to 17th century some 150 locally based rebellions. Initially peasants fought for the “ancient rights” (“stara pravda”). Later they were demanding changes in the feudal system. They did not achieve justice or major changes, since the courts were on the side of the upper class, however the injustices and unreasonable demands eased somewhat in time, since there was fear of further uprisings.

Slovenes in the 16th century

Their ethnic territory pretty much encompassed the borders of the present day Slovenia, with some of its ethnic territory within the environs of Trst and Gorica being ceded to Italy in the south, and Slovenian Carinthia to Austria in the north after World War I. It was a predominantly, an agrarian society with the feudal social structure, which gradually changed after the peasant uprisings of 14th, 15th and 17th centuries, in step with other western European countries.

The majority of population of Slovenian territories were farmers. However, unlike other rural populations in Europe of the time, Slovenes were unique in that they tended to combine the work on the land with other occupations – as tradesmen, merchants, innkeepers, blacksmiths, millers, artisans, drovers, ferrymen, carriers of goods on land and water. This was due to the geographical location of Slovenia on the crossroads between north and south, east and west and the direct route to the major port for the central Europe – Trst /Trieste. The society was diversified, and lived in villages, towns and cities, or participated in production, trading and educational work of the great monasteries, which were often considerable enterprises or centres of learning, as was the case of Stična monastery.

Great merchants established themselves in Ljubljana, and exercised great influence. There was Janez Lanthieri, who traded mainly in iron and cloth. He became the mayor of Ljubljana and was raised to nobility by the emperor in 1518. In 1527 he received the famous Lanthieri palace and estate in Vipava, which has been placed on the national cultural heritage list. In company with the merchant Lenart Praunsberger he traded in Italy, Hungary with a variety of goods. Another great merchant of Ljubljana was Vid Khisl, in turn mayor and judge, owner of a glass factory on the river Ljubljanica, copper smelting works (fužine), and several mills. He was received into peerage, became court counsellor, administrator of the region and great land-owner. He was a generous a supporter of Slovenian Protestantism and funded publication of books by Trubar and Dalmatin.

Humanism, reformation and birth of national awareness

In Slovenian history the 16th century marks the birth of Slovenian literary language and of the awareness of Slovenian identity than comes with the written language. The Slovenian speakers were divided as still are today into many dialects, some of them barely understood by others. It needed a literary tradition – a central standard speech to act as a unifying agent for all the various territories and create an awareness of a common identity. This happened for Slovenes in the 16th century with the emergence of Protestantism – in the extraordinary personality of the priest – Primož Trubar.

Protestantism was a watershed in development of Slovenian literary language. It began with the twenty-five books in Slovenian by Primož Trubar, published between 1550 to 1589, followed by the complete bible by Jurij Dalmatin, among the first twelve bibles in a national language, and the first Slovenian grammar by Adam Bohorič and dictionary of 4 languages by Hyeronimus Megiser, German school teacher and linguist.

He was the first in long line of educators, who actively involved themselves with education and enlightenment of the country people. He gave them first of all a Catechism, dedicated to all Slovenes, and at the same time Abecedarium (Primer) to tell them how to read Slovenian. For Trubar, literacy was the first step towards reading the bible and so towards independence of spirit. Reading in their own native language was the next step, which enabled Slovenes dispersed administratively and geographically to feel for the first time as one people.

His work reflects his religious reformationist and humanist zeal. He is also the first of the Slovenian tradition of national leaders. He is an influential personality of his time, and is asked by the Koper bishop and later protestant diplomat Peter Pavel Vergerij about his views on a broader south Slavic language.

Trubar contributed considerably towards reformationist literature in glagolitic and cyrillic scripts for Croatia, Slovenian Istria, and countries further east. He was on the other hand quite definite on Slovenian ethnic territory and Slovenian language. He left no doubt on the matter in a letter to the Duke Kristof von Wurtemberg (8 March 1580) He clearly defined the borders of Slovenian language and culture, which are even today the territories of Slovenian people. There is no doubt for him that Slovenes are a separate people with a distinct language, identity and culture, not to be merged with other south Slavic languages. In this he is the predecessor of France Prešeren, the first and greatest Slovenian poet, who also argued strongly for the distinct identity of Slovenian people – in the beginning of the 19th century.

Trubar was also a major reformer in religious matters. The publication of Cerkvena Ordnunga (Church Canon) in 1964 signals the change of Protestantism from movement into organization. All that was needed was the support of the Duke, to give it legal status. That however did not happen. The Duke was a staunch catholic, the catholic reformation began to take place, protestants were exiled and Trubar had to leave Slovenia never to return.

Only a very few protestant writings survived the counter- reformation: Dalmatin Bible and Bohorič grammar. Bishop Tomaž Hren, Slovenian catholic reformer was able to achieve confirmation in Rome of Dalmatin’s bible for catholic use. There were two reprints of Bohorič grammar in 1715 and 1758. Other protestant writings were less fortunate. They were all seized and burnt, only one single example of Cerkvena Ordunga and Catechismus survived.

Protestantism achieved response at various levels of Slovenian society, among tradesmen, and merchants, nobility and part of catholic priesthood. Small protestant circles were established in towns and cities, and gradually formed a Slovenian protestant church, which was defined when Trubar returned from German exile in 1561, and became its leader. The position of protestant faith changed with various secular and church leaders depending on their tolerance or lack of it, or religious orientation. By the end of the 16th century the principle “cuius regio, eius religio” was agreed upon. The ruler determined the religion.

Despite the war with Turks and other considerations, religious reform was enforced. from 1598. Protestant activities and organizations were banned. Those who refused to change to catholic faith were exiled. This spelt the end of protestant movement in Slovenia. What remained was the priceless gift of literacy and beginnings of national awareness.

Events in Slovenian territories in the 16th century: invasions, plague outbreaks, earthquakes, uprisings, reformation, counter-reformation, exile.

1499 Turkish invasions towards Venice, outbreak of plague

1510 earthquake in central Slovenia

1511 plague outbreaks over the whole country for several years

1515 Slovenian peasant uprising : for the ancient rights (“stara pravda”)

1517 beginning of reformation in Germany

1520 beginning of reformation in Slovenia

1526 -1560 Turkish incursions throughout Carniola, major battles for Vienna

1547 first persecution of protestants, Trubar in exile to Germany

1550 Trubar’s Cathechismus

1555 organizing protestant church in Slovenia

1560 -1564 Trubar the head of Slovenian protestant church

1564 beginning of major outbreaks of plague, continuing till the end of the century

1565 Trubar exiled

1573 the Slovenian-Croatian peasant uprising

1578 the peak of reformation in Slovenia

1579 beginning of counter-reformation in Slovenian lands

1582-1588 a series of Turkish attacks in the east, on Prekmurje

1598 exile of predicants, church organizations banned, counter-reformation commissions

1599 exile of protestant peasants and townspeople