Painter of emotional experience

From his early youth Rihard Jakopič (1869-1943) was drawn to art, spending his time drawing and painting from nature. While still a sixth form student at the Ljubljana secondary school he left his studies to devote himself completely to painting. He was later to say that he believed the Ljubljana fog awoke in him a presentiment of something akin to Impressionism. In 1887 he entered the Vienna Art Academy, leaving it after two years to study at Munich. Here too he stayed for only two semesters, and with other dissatisfied students persuaded the Slovene artist Anton Ažbe to found his own private school, which they joined. Ažbe was not committed to the Impressionist style, but neither did he oppose it, and he was especially good at encouraging the development of individual talents.

The art critic Isidor Cankar said of Jakopič that ‘he was destined to be born at a time when the creative force of the Slovenes was great, comparable to that which appeared towards the end of the 17th century. The painter initiated a temporal and socially organic continuity of Slovene art which permeated the sphere of national consciousness and became one of the desired attributes of national individuality…’

Of the four Impressionists Jakopič was considered by Cankar to be the deepest thinker, and the evolution of his work, which fell into three main stages, was correspondingly the most complicated. But as with Grohar, there was more than a slight element of contradiction in Jakopič’s character. He was not interested in artistic theory, believing that the source and problematics of painting lay in man’s soul, in the world of fantasy and imagination. But he worked according to the principles of his own ‘mission statement’ nevertheless, which in a typically Slovene manner underlined the dialectic opposition of impressionism and expressionism.

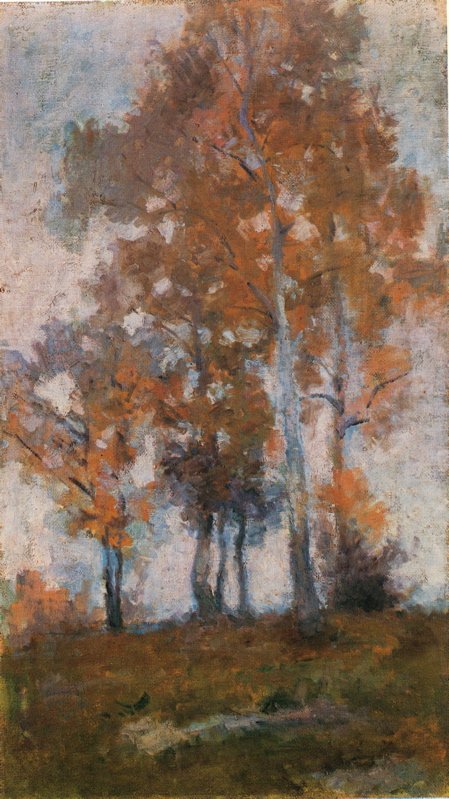

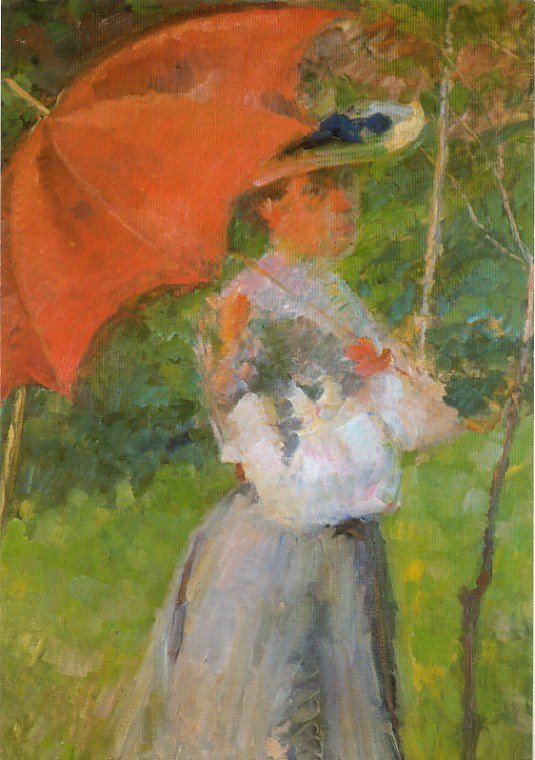

The first stage of his growth dated from the Munich years to about 1906, when he sought to achieve the accurate reproduction of nature through his apprehension of light and colour, as seen in the 1903 painting, ‘Birch-trees in Autumn’. His second phase fell in the decade between 1906 and 1917, when having mastered the means he no longer avoided intellectual content and worked on larger but more intimate figure compositions, where colour values were distributed evenly across the canvas; ‘Women Bathing’ (1910), ‘Memories’ (1912).

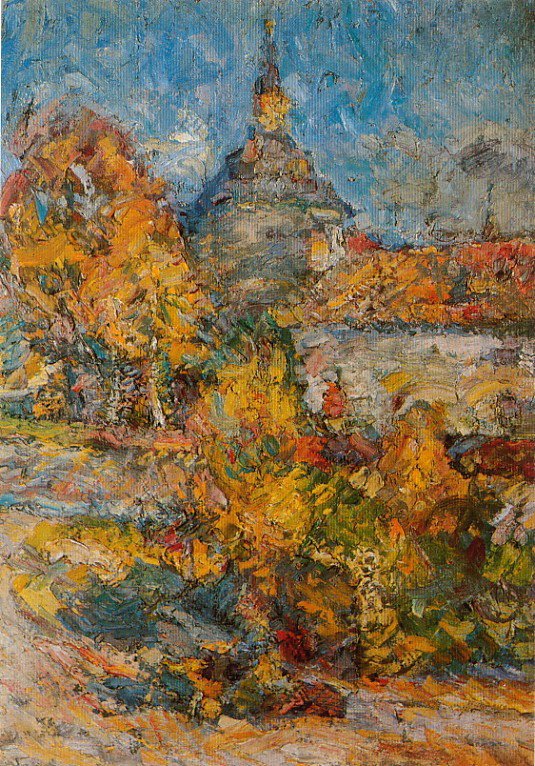

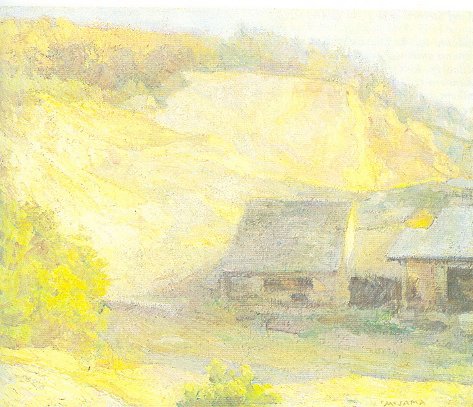

The third period extends from the end of WW1 to his death. At this time his work could be defined as ‘colour expressionism’, because colour became the medium of interpretation. The same material thus re-appears in different coloured compositions, representing different emotional interpretations. ‘The Sands’ (1919), ‘The River Sava’, ‘The Sava at Medno’, 1922.

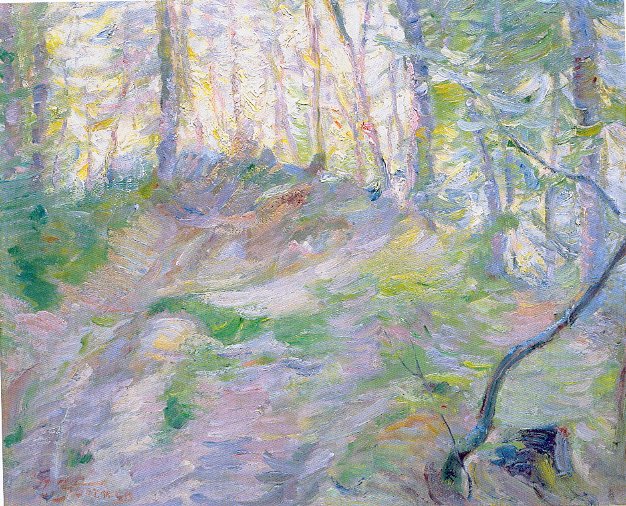

Jakopič also began to paint from memory, as though to reinforce both his beliefs and his style. The capture in paint of the optical impression, together with the illusionist qualities of colour applied to the canvas without any concern for the real form of the object, these were the vehicles of life which most interested the painter. ‘Don’t make an object’, he told his colleague Jama, ‘make a vision…’ From the beginning he had been inspired by the effects of mist on the landscape and the faintly discerned objects within it. He had compared these effects to dreams and visions which he wanted to bring to tangible life. For him the technique had been only a means, a personal confession its end. ‘I strove to digest the impressions of nature in myself and paint what I experienced’ he said.

Jakopič lived through colour. He considered it to be as palpable a medium as marble or wood is to the sculptor, or sounds to the musician. And although his thematic interest was broad, ranging between landscapes, still lifes, figural compositions, portraits and nudes – the purity and glorious vibrancy of his palette is most evident in his landscapes, where he began.