The pen in defence of the movement and its aims

Matija Jama (1872-1947) came from a middle class family and of the four artists had the most education, completing grammar school in Ljubljana and Zagreb and continuing his studies in law. Perhaps it was this that made him the most dogmatic of the impressionists and the only one to take up his pen to defend the reputation and truth of the movement and its aims.

During his sojourn in Zagreb Jama decided to abandon his law studies in favour of painting, attending private schools in Munich, and later the Academy. Influenced by Millet, he dreamed of a Slovene genre, and did illustrations for the magazine ‘Dom in Svet’ (Home and World) all the while discussing the new painting with Jakopič. But despite sharing some common ground with his colleagues his experience of Impressionism was different to theirs, being more doctrinaire and systematic to the point of scientific analysis. ‘The main problem of realization,’ he was to declare, ‘lies in the right solution of reciprocal tone relations. The ‘colour mood’ is something concrete, however exterior technical form is given to this experience only by scientifically founded tone and light painting. Artistic perception can only be subjective, but the expression and formation of the means chosen should not be arbitrary since it is dependent on the existence of laws of objective physical and natural reality.’

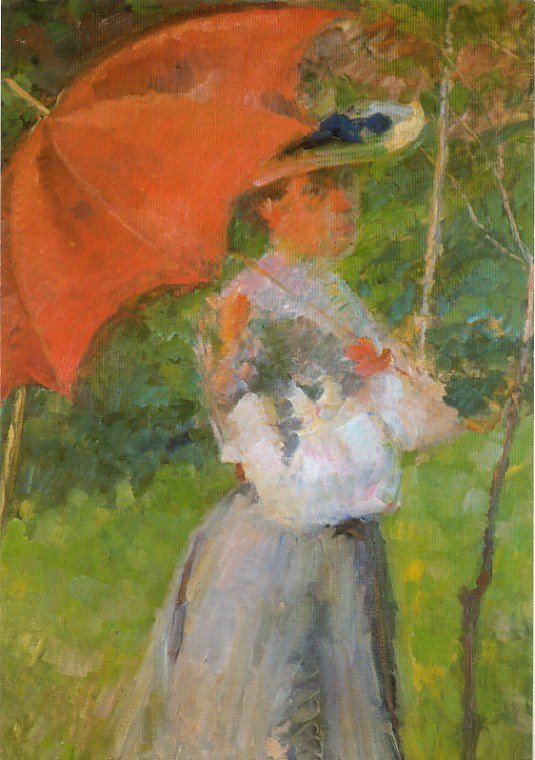

Jama was interested above all in the objective registration of natural phenomena: Nature and its impression was his standard, but the painting was intended to make an impact on the eye, not the intelligence. In this he differed diametrically from Jakopič, who also searched for the Slovene expression in art but whose work ultimately reflected his experience of the object, rather than the object itself.

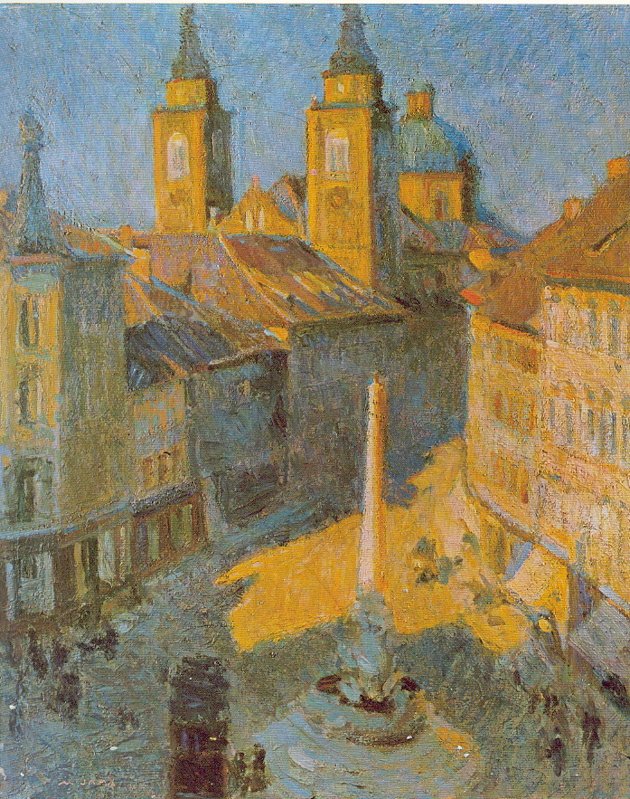

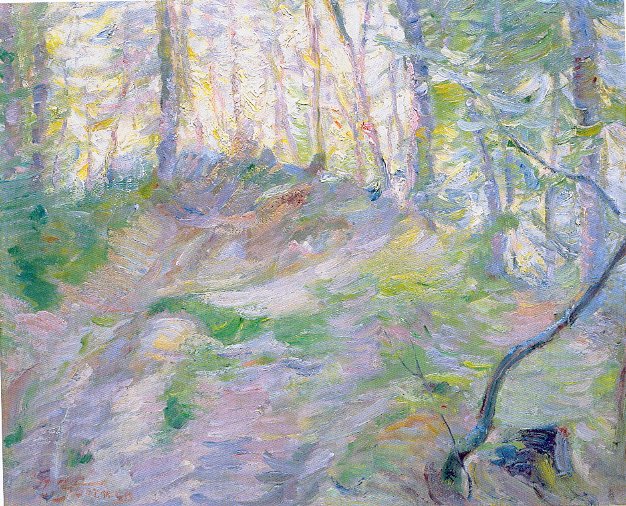

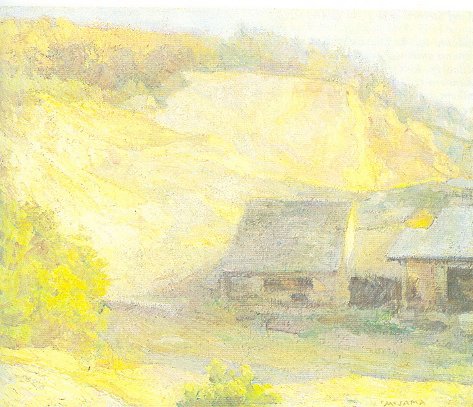

Jama considered that only by painting outdoors and in full daylight would he achieve his goal, and remaining faithful to his personal ideal he succeeded in producing pictures that are breathtakingly luminous, like ‘Stone Quarry’ 1907. Jama applied paint to canvas more sparsely than did Jakopič or Grohar but this did not detract from the translucent effect. Nor did the colour values of shadows and darknesses, which also had their place in the overall scheme, as is seen in ‘Bridge on the Dobra’ 1907, and ‘Ljubljana Town Hall Square,’ 1930.

Jama’s artistic evolution fell into three main periods. The first was Munich, when as early as 1897 he declined the aesthetics of classicism and proclaimed nature the only true teacher of artists. The second period was one of struggle as he sought to capture the impressionist image of the world. The final period, from 1910 until his death in 1947, is one of sovereign mastery of the method, like the delicate ‘Fruit Orchard in Snow’ 1940. His interest was not only the landscape with its atmospheric light and variety of colour effects, but at one with all it contains, as in the painting ‘Round Dance’ (Kolo) 1935. His favoured themes were the Slovene and Croatian countrysides, and he was unsurpassed in conveying their Arcadian character.

From 1940 until his death there was a gradation of this mood to forms in which impressionist reality changed to a fantastic expressiveness. Nature viewed through the artist’s temperament provided a new challenge, but was unrealizable in terms of pure Impressionism.

In his time Jama defended the Impressionist movement against accusations of sterility, comparing its achievements to the discovery of perspective; and while he admitted that the group’s method could not be the final form of Impressionism, he held that what they discovered about light and colour would be the foundation of modern painting.