The reality beyond the visible,

sensible world

As a painter Ivan Grohar (1867-1911) was most like Jakopič in spirit, though their backgrounds differed. He had grown up in the farming community of Sorica where handicrafts like painting on glass and bee-hive fronts were still very much alive. But it was his first acquaintance with Italian art reproductions that made him dream of being an artist himself. The village priest recognized his talent and in 1888 sent him to the church painter Matej Bradaška in Kranj. Grohar was later to go to Zagreb, Graz, and finally Vienna, where the Academy refused him admission on grounds of his lack of education. Returning to Slovenia he met Jakopič who in 1895 led him to Ažbe’s school, and his career was launched.

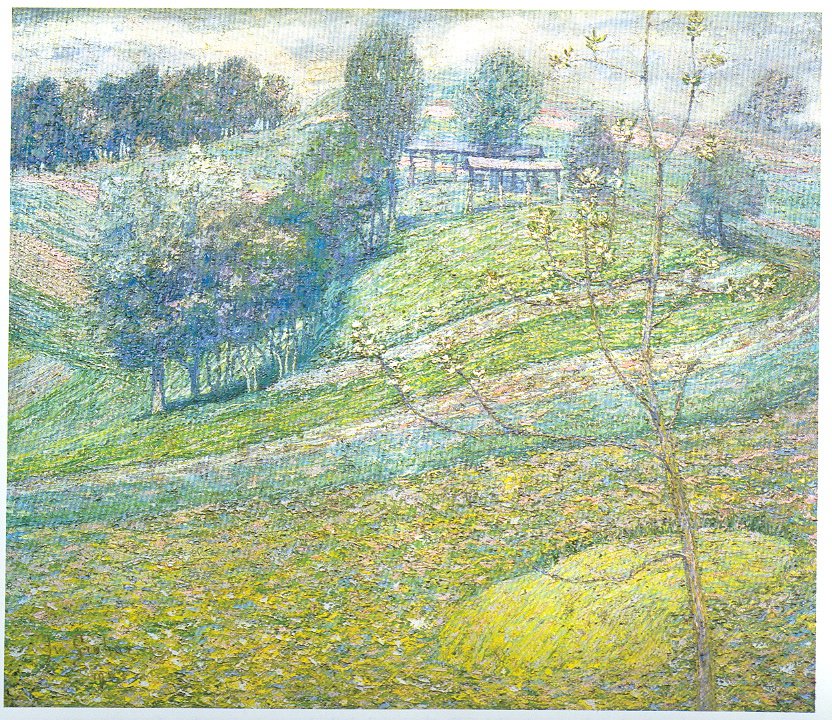

Initially a painter of portraits and peasant genre scenes Grohar also became known for altar pictures and received many orders. Like his compatriots he favoured impressionist techniques and Segantini’s pointillist style became a point of departure for him, with the palette knife as his favoured tool. This is most noticeable in paintings like ‘Spring’ and the autobiographical ‘Larch’. Originally a larger painting, ‘Larch’ was later reduced from a rectangular to a square frame by the artist. The tree not only became the central object, it also effectively divided the scene into two parts. It was a personal statement and a telling comment on Grohar’s own contradictory character, further underscored by his signature on the trunk.

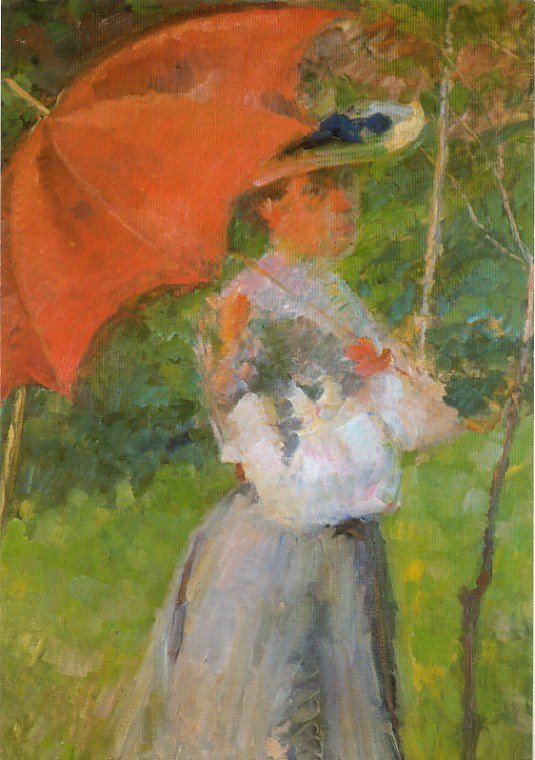

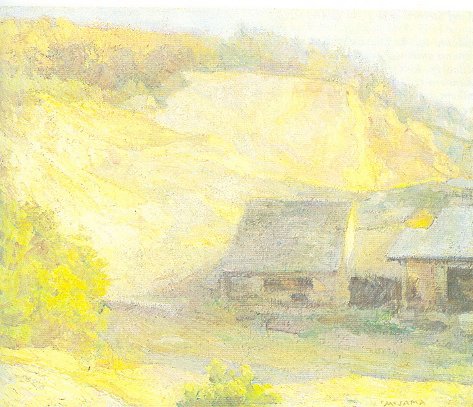

The artist’s style was paradoxical yet harmonious, uniting opposites in a way which was and remains unique. His figure compositions and themes of country life are imbued with the same sense of harmony. Art historians often refer to the lyrical and transcendent qualities of his work which they see as the natural expression of an innate mysticism; a state of mind that found support and confirmation in Jakopič’s definition of art as a dream or vision. Grohar’s technique was dynamic and unconventional. Resembling silk embroidery or jewel-encrusted cloth, the dense application of colour emphasized the physicality of both painting and subject matter, but at the same time it ‘de-materialized’ them, the technique creating a shimmering effect as if the subject was a mirage, a ‘vision’. Set in the context of nature, country folk shared in its beauty and benevolence, becoming one with it, as in the painting ‘Sower’, where the figure merges into the shimmer around him, landscape barely defined by a solitary hayrack. The background is strangely ambiguous, as if lacking depth, and this, together with the painting’s overall golden tones recalls the flat gold surfaces and symbolic values of Byzantine icons.

‘Škofja Loka in the snow’ is perhaps Grohar’s most remarkable painting, one in which eternal nature and the work of perishable human hands appear indissolubly joined. No-one before him had so vividly depicted a snow-storm, the drift of snowflakes which obliterates familiar forms while creating new shapes and perspectives. Yet although the painting truthfully portrays an atmospheric moment, it is not a moment registered in time as occurs with a photograph. The issue here is the portrayal of motion, of movement that will last as long as the material substance of the painting lasts. Grohar recognized a reality beyond the visible, sensible world, and within the parameters set by the painting he effectively created a sense and an illusion of both time and motion, abstract concepts which paradoxically encapsulate the finite and infinite, the temporal with the eternal. And in so doing he went far beyond the normal standards of creativity.

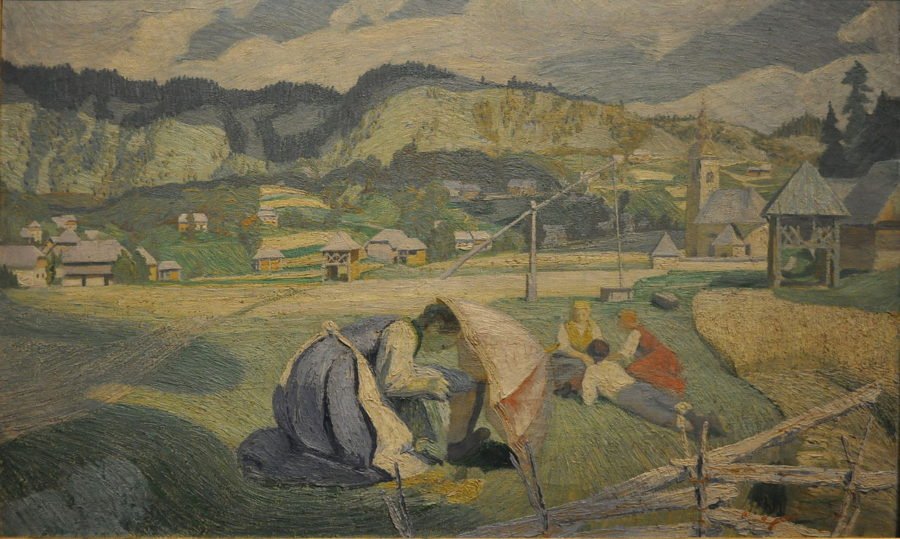

Grohar was later to adopt a broader more expressionistic style to emphasize the intended symbolism. In ‘Potatoes’ the pyramidal arrangement of the foreground figures echoes the outline of the mountain in the background; the sense of weight is juxtaposed against the opposite notion of weightlessness, tension against ease. In this way the artist suggested that even a life of physical labour has a value that transcends the mundane.

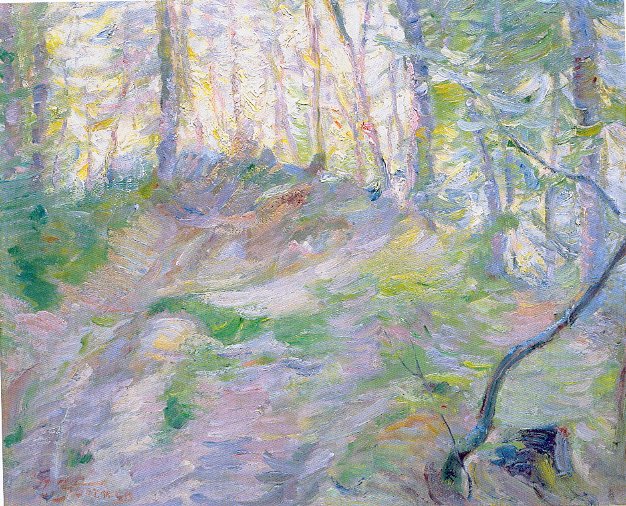

In the enigmatic ‘Shepherd’, painted some time before Grohar’s premature death in 1911, the artist juxtaposed complementary concepts of stillness and motion, time and eternity. In earlier works the painterly surface seemed to vibrate with life; here the looser and longer strokes are slightly winding, suggesting the slowing down of movement before the still figure of the shepherd. The scene is simple but no less powerful, the intensity of life now interiorized.

Poor throughout his life and beset with professional disappointments, Grohar would appear a tragic figure were it not for his paintings. Perhaps he had reason for his work to be dark and despairing yet it is not. At best, some express a quiet melancholy, but overall they are illuminated with a sense of optimism and love for the country of his childhood. He created most of his best works in the first decade of the 20th century, the period of the Škofja Loka school, and because his output was small they seem all the more significant and intense: Spring (Pomlad) in 1903, a vision of a sunlit landscape which became a national image at the Vienna exhibition, and assured Grohar’s status: Larch (Macesen) 1904; the extraordinary ‘Škofja Loka in snow’ (Škofja Loka v snegu) in 1905; Sower (Sejalec) 1907; Potatoes (Krompir) in 1909; ‘The shepherd’ (Črednik) 1910 among them.