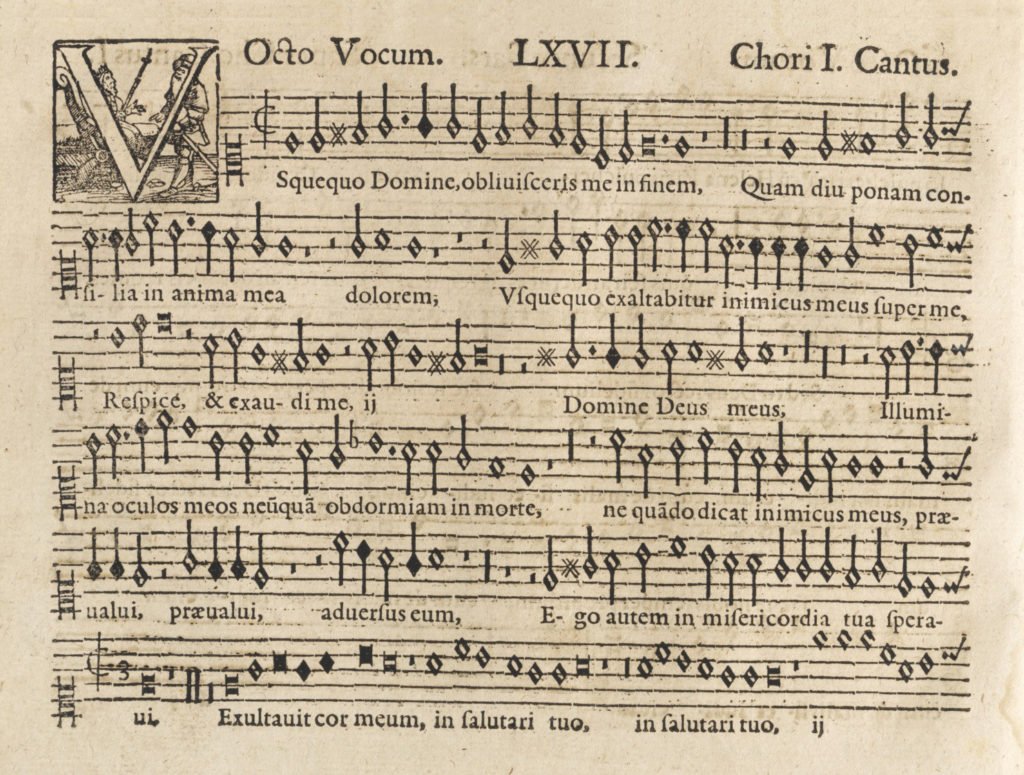

Individualism and affective representationGallus adopted many techniques which were considered original and unconventional at the time and distinguished his work from that of his contemporaries Palestrina, Lassus, and Victoria – harmonies, ‘madrigalisms’, chords, the use of progressively shorter figurations, the many alterations in each work, the primacy of some of the voices, particularly the cantus, the divided choirs.

‘Baroque’ is a term used generally to designate a period or style of European music covering the years 1600 to 1750. The word is derived from the French ‘baroque’ which comes from the Portuguese ‘barroco’, meaning a pearl of irregular shape. Some traits characteristically baroque are dynamism, ornamentation, sharp contrast, individualism, but most of all, affective representation. From the 1540-s to the 1740-s, composers strove for the expression of affective states in most of their works.

Gallus adopted many techniques which were considered original and unconventional at the time and distinguished his work from that of his contemporaries Palestrina, Lassus, and Victoria – harmonies, ‘madrigalisms’, chords, the use of progressively shorter figurations, the many alterations in each work, the primacy of some of the voices, particularly the cantus, the divided choirs.

Chord Music

Gallus preferred ‘vertical’ music to the linear, and sacrificed the melodic line for the sake of a better ‘colouring’ through harmony. Thus his melodies often emerge from a succession of harmonies (rather than the reverse), and there are in his scores many melodic intervals ‘forbidden’ by the theoreticists of the time. The following are examples of leaps not separated by a silence, nor belonging to the same chord.

- diminished third in the altus of the Mirabile Mysterium OM 1,54: measures 44-46.

- melodic augmented fourth in the cantus of the Lamentatio VII, OM II,23: measures 79-80.

- diminished fourth. Several leaps in Mirabile Mysterium, OM 1,54: measures 56-60.

- diminished fifth in the cantus of Resonet in laudibus, OM I,59: Compasses 52-53.

- increased fifth in the tenor of the Lamentation II, OM II,18: measures 69-71.

- major sixth in the tenor II of the Benedictus Deus Pater, OM III,14: measures 30-31.

- minor seventh in the cantus of the Te Deum, OM III,24: measures 34-35.

- major seventh in the tenor of Lamentatio IV, OM II,20: measures 74-77.

Gallus used the tritonus, (‘diabolus in musica’) in most if his works and in various ways, sometimes also the quadritonus, as at the end of the Agnus Dei in the Missa Caste novenarum (SQM I.4).

Harmonic relationship between voices

There are countless cases in which the movement of the voices is conditioned by the succession of chords, creating cadences of a ‘baroque’ character. They are usually the seventh connection of the dominant with the first grade (conclusive cadence), and also of the seventh of dominant with the super-dominant (suspended cadence). Gallus often uses the latter device at the end of his compositions, a little before the final cadence: they are usually also the seventh connection of the sensitive and the tonic. On the other hand, the succession of different chords are also common, as for example subdominant – dominant – tonic. Other examples are:

- succession of accordance V7 – VI – IV – V7 – I 6/4 – V – I , in Sapientia clamitat in plateis (OM I,25).

- succession of accordance V – V7 – I 6/4 – V – I , in Omnes de Saba venient (OM I,55).

- succession of chords IV – V7 – I 6/4 – V – I, in Or bone Iesu, illumina oculos meos (OM I,92).

- succession of chords IV – V – V9 – I, in Lamentatio VII, (OM II,23).

- succession of chords II – V7 – I 6/4 – V – I , in Cum Rex gloriae Christus (OM II,30).

Sometimes Gallus used procedures that were before their time, like the sequential seconds between two voices in the Lamentatio IV (OM II,20), measures 103 and 104.

The use of shorter figures and the triplet

Beginning with the Opus Musicum, Gallus used progressively shorter figures. There are examples in the OM of four quavers (fusas) each assigned its respective text, and of note alteration, as in the motet super flumina Babylonis (OM III,49), measure 40. Gallus first availed himself of the fusas in the motet Iubilate Deo omnis terra (OM III,48), measure 34. In some passages Gallus used both binary and ternary measures, and by placing the number three (3) above three minims or semi-minims indicated that the three notes should be sung in the time corresponding to two figures of the same type. First used in the motet Stella quam viderunt magi (OM I,38), measures 27 to 29.

Importance of the bassus

The task of singing the fundamental of the chord was assigned to the heaviest voice, the continuous bass. In works composed for ‘sharp’ voices (ad aequales) Gallus always called the lower voice the bassus, even when sung by a contralto. In these cases the contralto established the harmonic base of the chord, and sometimes duplicated the voice of the bassus in the last note of the composition, as for example in the Lamentatio I (OM II,17) where after the first intonation, Gallus directs the bassus of Chorus II to sing an octave above the bassus of the Chorus I, while the others sing in unison, in this way filling the chord.

Interdependence of the voices, with the supremacy of the ‘sharp’voices

From the OM, the title of cantus was transferred from the tenor to the higher voice. An example of the dependence toward the soprano is found in the sequential third and sixth, as in Christus surrexit (OM II,39, measures 1-6). Gallus opened his polyphonic works with the cantus 45.9% of the time: the altus 19.3%, the tenor 25.3%: the bassus 9.4%.

Alterations

In his sacred works the composer frequently used note alteration to provide ‘colouring’, to the extent that of the twelve sounds in the scale, ten or more are used 88.1% of the time.

‘Madrigalisms’

The quantity and quality of expressive techniques used are surprising. In the Mass the crucifixion and death of Christ were suggested with a descending melody, the Resurrection with an upward one. In the motet Venite ascendamus ad montem Domini (OM 1,2) the higher voices express the notion of ascent, while the tenors move in such a way as to suggest the mountain top. Another most unusual example is the concluding second part of the text ‘cuius regni non erit finis’ in the motet Ecce concipies (OM 1,24), where the choir repeats the phrase kingdom without end five times, then ends the final chord on a minim, giving the sensation that the work hasn’t an end. But the motet Mirabile Mysterium (OM 1,54) is possibly the most original of all. Apart from the radical chromatism, Gallus employs melody to ‘paint’ words, as with the text homo factus est with its octave leap and smaller interval to suggest that God came down from Heaven to become man.

Other examples are found in the motet Ascendit Deus in iubilationes (OM II,48) where Gallus reproduces the sound of trumpets for the text ‘in voce tubae’. Before this the voices sing an ascending melody to describe God’s ascent into the heavens to shouts of joy. The motet Qui manducat meam carnem (OM III, 18) is also for five voices ad aquales, which mingle in florid polyphony to suggest permanence (of the text the one that eats my flesh and drinks my blood will remain in me and I in him).

All the musical examples are taken out of the edition MAMS – Monumenta Artis Musicae Sloveniae, published by the Academy of Arts and Sciences of Slovenia, Ljubljana, 1985-1996.