Yuri Venelin (1802-1839) was Russian and the first historian of the Slavic peoples on European territory. He maintained that European history had been written almost exclusively from the Roman or German point of view, ignoring the presence and influence of the Slavic peoples of Europe.

Venelin began his research by investigating the Bulgarian people. His pioneering work was published in Russian with the title The Ancient and Present-day Bulgars (1829). It was the first systematic investigation of the history of this eastern Slavic nation and earned the young historian a great deal of acclaim by the leading Russian historians. It also led to the establishment of Slavic Studies at Moscow University.

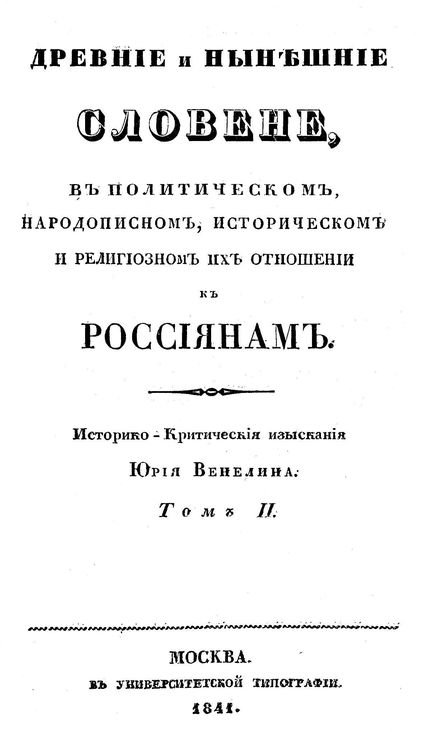

Yuri Venelin then turned his attention to Slovenes, the Slavic people occupying the region south of Vienna as far as the Istrian peninsula, and Venetian Republic in the west. His research on Slovenes was later published as the second part of the book on the Bulgars, with the title The Ancient and Present-day Slovenes (1840).

In preparation for his history of Slovenes Yuri Venelin read all the works of Slovenian Enlightenment, the philologist Jernej Kopitar, the historian Anton Linhart, Slovenian polyhistorian J.W. Valvasor, the Serb Vuk Karađić, the Croat M. Katančić and all the available literature by the German authors of the time. Yuri Venelin died prematurely in 1839 before he could finish his book. It was subsequently completed and published by his cousin and associate Ivan Molnar.

The work was first published in Slovenian in 1992, republished in 1996 and reprinted in 2012 with the title Starodavni in današnji Slovenci (transl. The Ancient and Present-Day Slovenes).

The following is an excerpt from The Ancient and Present-Day Slovenes, translated from Slovenian by A.L. Ceferin

The settlement and the inhabitants: their language with dialect variations, and the ancient origins of their name.

Today Slovenes occupy the lower part of Štajerska (Styria), there are more than 300,000 in number, lower part of Koroška (Carinthia) 100,000, (the upper parts of these lands have been settled by German colonies and are partly Germanized. In Kranjska (Carniola) there are over 350,000 inhabitants, and in the western neighbouring counties of Hungary more than 50,000: altogether they number more than 800,000. The inhabitants of Štajerska, Koroška, and Hungary call themselves Slovenci (Sloventzi): Krajnci (Kraintzi) are the inhabitants of Kranjska. The language of all these is one dialect. In Kranjska we can detect two kinds of pronunciation. The lower Carniolan pronounces U instead of O, eg. kust, slabust, dobruta, si vidil muja mater, pshenizu na prudaj pejlem instead of kost, slabost, dobrota, si videl mojo mater, pšenico na prodaj peljem: in contrast, the upper Carniolan is too attached to O, often using it instead of U, eg.: proti sonco (sonzo), instead of soncu (sonzu), kaj mo je instead of kaj mu je. Ljubljana is the boundary between these two dialect shadings.

Another territory of Slovenia, the north-west Hungary, consists of Slovaks, in some areas with colonies of up to 1,000,000. Their language is another Slovenian dialect that leans towards Czech and Polish. Germans call the first Winden (general name) and the second Slowaken. Due to the similarity of the names Slovenci – Slovaki, we regard them as one tribe with the name Slovenci, who are separated by the river Danube.

At this point we won’t discuss the reasons why Slovaks moved away from Slovenes, and drew closer to Czechs in their speech. We will say more about it later. Firstly we will review the so-called Slovenci.

The name Krajnci (Krainzi/Carniolans) taken up by one region of Slovenija is not a clan or lineage name, but territorial or geographic designation. It is used in similar manner as the word Ukrajina. Some maintain that this is derived from the word kraj (place), meaning the land or country, others believe that the word means the furthermost part, the periphery i.e. the border. Russia and Poland both gave this name to Ukrajina, as the land that represents the boundary against the foreign tribes, the Tartars and the Turks. Slovenes in the south acted similarly, when they were faced with Arnauts (Albanians) on one side, Italians on the other. They named their own borderland Krajina or Ukrajina.

The name Krajina is ancient in Slovenian tradition, as old as their self-awareness. Romans gave the name Carnia to Slovenian Krajina, and called the inhabitants Carni.

If we had to name some of the mentioned lands in this year of 1834 and the Illyrian kingdom itself according to its inhabitants, then we would have to call them Slovenia, Slowenenland, la Slovenie. This name is as alien to the Russian, Czech, Polish, Serb and the Bulgar as the Tatar, Kalmik, German or Greek. Try to call a Russian peasant a Slovene, and wait to hear what he will say. Slovenian dialect (speech) is distinct from the other Slavic dialects or languages:

Slovenian is not Czech, nor Serbian, nor Polish, nor Croatian, not in name and not in language; not in dress, not in character nor history.

Schaffarik (Geschichte der Slawichen Sprache und Literatur nach allen Mundarten, 1826) recorded several Slovenian works of literature. The first books in Slovenian language were published during the Reformation. Primož Trubar printed several books in Tübingen after 1550; among them was the New Testament. Subsequently Jurij Dalmatin published his translation of the bible in the “true” Slovenian language (pravi Slovenski jesyk). These translations were pioneering works in the development of Slovenian literary language and initially drew scholarly criticism. In the opinion of scholars Trubar’s Slovenian was marred by the use of numerous words of German origin and Dalmatin exhibited what was regarded as a somewhat ecclesiastic style.

Consequently Jurij Japelj (Georgius Japel) and Blaž Kumerdej (Blasius Kumerdej) prepared a new translation of the bible and published it with the approval by a committee of Slovenian scholars. This was regarded as the translation “in the proper and true Slovenian people’s language”.

Reference: Jurij Venelin, Starodavni in današnji Slovenci, Ana Brvar, et.al. (transl. from Russian to Slovenian), Amalietti & Amalietti, Ljubljana, 2012.

Aleksandra L. Ceferin