Religious reform, literacy and national destiny

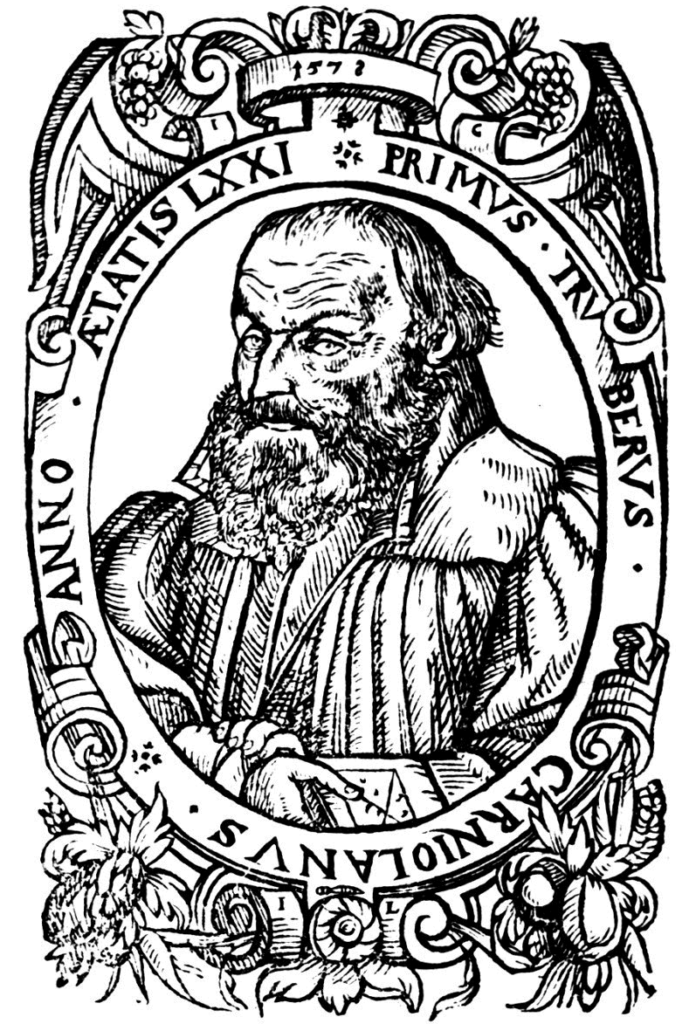

There are pivotal events and personalities marking evolution of Slovenian people into a nation. The first recorded and seminal event was the investiture of the knez (Duke) on the field of Gospa Sveta in Carinthia, northern Slovenia in the 6th century. It was so powerful that the ritual in Slovenian language endured till the 18th century. The second significant record are the first Slovenian written texts traced to 8 to 10th century, the so-called Brižinski spomeniki (Freising Manuscripts). The third defining event in Slovenian history is the emergence of reformation and its Slovenian guiding spirit – Primož Trubar. With his insistence that Slovenes should comprehend the teaching of their faith and worship in their own native tongue, he lay the foundation for the script, vocabulary and grammar of Slovenian language, and thus made way for further development of Slovenian language, literature and a unifying national identity.

Primož Trubar was born in 1508, the son of a prosperous miller and carpenter. The small village of Rašca, in Dolenjska (Lower Carniola) was located on a busy crossroads of routes leading eastwards and to the coast. Primož left his home village and studied in Reka (1520-1521), and later in Salzburg (1522-1524). He acquired his first truly humanist education in Trst (Trieste) at the Palace of the Bishop Peter Bonomo, where he earned his living as church singer and personal secretary to the bishop. The nature of his studies is evidenced by his quotations of Virgil, Erasmus of Rotterdam and Jean Calvin.

In 1528 the parish revenues which Bishop Bonomo secured for Trubar, allowed the twenty-year old to continue his studies in Vienna. He did not finish his courses there. In 1529 lectures were discontinued due to the invasion by the great Turkish army, which had advanced as far as Vienna.

In 1530 Trubar returned to Trieste. He was ordained into priesthood by the Bishop Bonomo, who granted him the post of vicar of his parish in Laško. In 1535 Trubar was appointed to the post of cathedral priest in Ljubljana, but once again had to seek refuge in Trieste. His reformation inspired sermons, and particularly his stand against pilgrimages and construction of new churches had provoked a fierce reaction. Trubar remained in Trieste for two years, making for himself a name as a Slovene preacher. Under the guidance of Bishop Bonomo, and as a member of his circle he was broadening his education and refined his thinking on reformation. Trubar participated in discussions of the Bishop’s circle, who read and discussed the works of Erasmus of Rotterdam and other humanists.

Due to the intrigues of Peter Pavel Vergerio, bishop of Koper, Trubar eventually had to move to Celje, to the benefice awarded him by Bishop Bonomo.

It was due to his patron, who had considerable influence at the Vienna court and with the consent of the liberal bishop of the time Ivan Kacijanar, that he was able to return to Ljubljana in 1542, and the appoinment as canon.

By 1547 Trubar was again in exile. Urban Tekstor, the next bishop of Ljubljana and staunch catholic, strongly disapproved of his reformationist tendencies. This time Trubar was excommunicated by the ecclesiastical court, and his property, together with a substantial library, confiscated.

It was a turning point in his life. Except for shorter periods of time, Primož Trubar was to spend the rest of his life in exile in Germany. However, he would not give up his mission among Slovenian people, and made a decision that would occupy him for the rest of his life and leave a unique legacy. He decided that he would fulfill his mission by publishing and printing books in Slovenian language.

In 1550 he completed his first Slovenian book – Cathechismus. It was printed in Tuebingen and was available in Ljubljana in the spring 1551, simultaneously with Abecedarium (Primer). He dedicated it to all Slovenes: “Vsem Slovenzom Gnado, Myr, Mylhost inu prauu Sposnaneboshye skusi Jesusa Christusa prossim” (To all Slovenes mercy, peace, grace and true faith through Jesus Christ, I pray).

Trubar’s aim was to offer God’s word to Slovenian people in the language in which they communicated and thought. However, the feeling that comes across from all his dedications and introductions is that of great love for his people and his native language. He means all Slovenes, whatever their regional name, and whatever their local dialect.

It was an enormous undertaking, requiring decision about an appropriate script (his first two books were in the gothic, the following publications in the latin script), codes for Slovenian sounds, and most importantly about the choice of dialect, that would be most accessible to all the speakers of the great range of Slovenian dialects.

In 1553 Trubar commenced his posting as preacher in Kempten and began translating the New Testament into Slovenian language. He began with The gospel of St.Mathew (1555), then published the second revised edition of Cathechism and Abecedarium. In 1557 he completed one of his most important works Ta pervi deil tiga noviga testamenta (“The first part of the New Testament”), Hishna postilla (House Postila) and Slovenian calendar. St. Paul’s letters to Romans was published in 1560, and St.Paul’s letters to Corynthians and Galatians in 1561.

From 1561-1565 Trubar became the Head of Slovenian protestant church in Ljubljana. During this period he published books in glagolitic and cyrillic scripts for Croatian and Serbian public. In 1562 he arranged Artikule ali dele prave stare vere (Articles or parts of the true old faith), and in these gathered three protestant creeds.

His major work and most significant reformationist work was Cerkovna Ordnunga (Church Canon), published in 1564. Trubar above all argued for Slovenian language in church worship. He urged the government to establish a Slovenian education system, with the recommendation that each parish employ a teacher.

In 1565 he was exiled again, for a time parish priest in Lauffen and then in Derendingen. He continued writing and publishing, completing the second part of the New Testament and several Slovenian hymn-books. Just before his death in 1586 he translated Luther’s House Postille (collection of sermons and meditations).

Trubar’ s Achievements

In his life Trubar wrote altogether more than 20 Slovenian books, 2 German books, 10 German forewords, and dedications for Croatian books published in Glagolitic and Cyrillic scripts. His works reflect his religious reforming spirit and pedagogic educational zeal for his people, whom he wanted to see enlightened and spiritually enriched. He preached the return to the true Christian faith and opposed building the hilltop churches. Since the only true faith is contained in the Bible everyone should learn to read and worship God in their own mother tongue. From the beginning he saw the need for schoolbooks, translations of the Bible, and hymn books and did his best till the end of his life to rectify that lack.

Significantly Trubar also resisted tendencies, repeated in the following centuries, to amalgamate Slovenian speech with the other south Slavic languages, creating one single central literary language. Like the great Slovenian poet France Prešeren in the first half of the 19th century, he saw Slovenian people as linguistically and culturally separate, having clearly defined the borders of their ethnic territory, which have remained unchanged till today.

Trubar’s influence and significance in the evolution of Slovenian literature is extraordinary. He was an exceptional man of his time. Priest and disciple of Martin Luther, he was one of the leading circle of Europe’s reformationists, revered within his own country and respected beyond its borders. It has been said of him that his work and influence has been of a columbian significance and impact. At the birth of modern Europe he had established Slovenes as an entity within the western European culture and civilization. With the codification of the literary language he made possible the development of Slovenian national integration, and the same time provided a foundation for Slovenian culture and Slovenian literature, which ultimately shaped the Slovenian national identity. His greatness exists in the fact that he firstly recognized a favourable historical point of time, and secondly that he provided suitable pathways, making possible the development and broadening of Slovenian spiritual identity, which has continued till the present day.

Trubar’s legacy to the following generation

Sebastian Krelj (1538-1567), born in Vipava was the most highly educated of all Slovenian protestants. Beside Latin he knew Greek, Hebrew and Croatian language and glagolitic literature. He was knowledgeable in linguistic and theological matters. He was in turn Trubar’s assistant preacher in Ljubljana, and later superintendent of Slovenian protestant church. In 1966 he published Otročja biblija (Children’s Bible), and in 1967 Postila slovenska (Slovenian Postille),with a Slovenian foreword. He put the central dialect into context of dialects spoken by Istrians, Vipavians and Lower Carniolians, who “all speak a purer Slovenian than Carniolans, who mix in many German words”. He improved on Trubar’s language, mainly by avoiding germanisms and the use of the article, and he exactly identified and used the signs: s, z, c, š, ž, č, and introduced signs for semi vowel and narrow e. His reforms were taken up by Dalmatin in the bible, and Bohorič in the grammar.

The most significant of Trubar’s followers was Jurij Dalmatin (1547-1589). He was born in Krško, where he attended Bohorič’s school. With assistance of state scholarships and support of his mentors Bohorič and Trubar, he completed tertiary studies in Tuebingen, Germany, where he received his master’s degree in philosophy and Protestant theology. From 1572 he was appointed Slovenian and German preacher in Ljubljana, supervisor of state school, court preacher, member of Carniolan protestant church council, visiting priest of protestant parishes and parish priest in Škocjan near Turjak.

Dalmatin wrote a great deal. He has several publications to his credit, including participation in some of Trubar’s books. However his greatest work is the complete bible in Slovenian language, The so-called Dalmatin Bible. It was printed in Germany and published in 1,500 copies in 1984, after the Slovenian printer in Ljubljana was closed down. Of these the great majority was smuggled to Carniola. It was one of the most beautiful of the protestant books, its cost the price of a pair of oxen.

Finances for the printing came – the cost was 6,000 gold dinar – from Carniolan, Carinthian and Styrian nobility. A special committee inspected Slovenian text for correctness by comparing it with Luther’s translation, as well as Hebrew and Greek originals.

Dalmatin could not have undertaken this work, without his predecessor Primož Trubar. However there is improvement in choice of vocabulary, expressions, less germanisms. He was evidently linguistically more skilled than Trubar, and had begun to introduce the orthographic reform of Sebastjan Krelj.

The significance Dalmatin’s bible was such that catholic priests used it for another 200 years. It served as the basis for all subsequent translations and is rightfully regarded as the founding stone of Slovenian literary language.

Another associate and friend of Trubar, who made his mark on development of Slovenian language in the 16th century was Adam Bohorič. His great contribution to the history of Slovenian nation is the first Slovenian grammar and the linguistic input into the first complete bible in Slovenian language – the Dalmatin Bible.

In 1592 Hieronim Megiser, German school-teacher, speaker of several languages and polyhistorian, a school friend of Dalmatin’s, published the first dictionary of four languages, Latin, German, Slovenian and Italian – Dictionarium quatuor linguarum. It was reprinted three times. Words were taken from the Dalmatin register, Bohorič grammar and collected from oral usage of several Slovenian dialects.

In the following centuries little was published to continue Trubar ‘s literary tradition. The counter-reformation movement in Slovenian territories was vigorous, aimed to eradicate all traces of Protestantism in the region. A few protestant writings in Slovenian survived the counter- reformation: Bohorič’s grammar, Horulae arcticae (Winter Hours) and Dalmatin Bible. Only a very few of Trubar’s publications were saved from the holocaust of wholesale burning. There is only one copy of Cathechismus and one copy of Cerkvena ordnunga still in existence.

However the achievements of protestant writers laid the foundation for Slovenian literary language, and sowed the seeds that grew in the following centuries and eventually bore a magnificent harvest.

The most significant of Trubar’s works:

1550 – Catechismus (with hymns), Abecedarium

1555 – Ta evangeli sv. Matevža – The Gospel of St. Mathew

1557 – Ta prvi dejl tiga noviga testamenta – The New Testament Part I

Ta slovenski koledar – Slovenian Calendar

1558 – En regišter….ena kratka postila

1560 – Ta drugi dejl tiga noviga testamenta- The New Testament Part 2

1561 – Sv.Pavla ta dva listi – Two letters of St.Paul

1564 – Cerkovna Ordninga – Church Canon

1566 – Ta celi psalter Davidov

1567 – Ta celi Katekismus, sv Pavla listuvi – Complete Cathechism, Letters of St.Paul

1575 – Tri duhovske pejsni – Three church songs

1577 – Noviga testamenta posledni dejl – New Testament Part 3

1579 – Ta prvi psalm ž nega trijemi izlagami – The first psalm with interpretations

1582 – Ta celi novi testament – The complete New Testament